Do We Need a Recession Because Wages Are Too High? 5 Responses Answering No.

A survey of the universe of responses pushing back on the idea that wages are so high we need a recession to bring them down in order to tackle inflation.

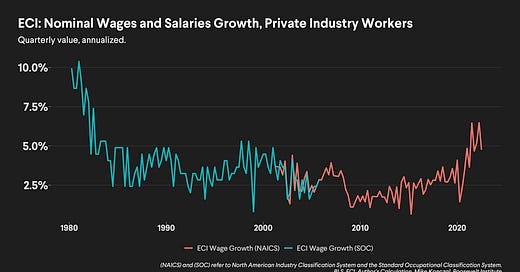

During the first three quarters of 2022, nominal wage growth, as measured by the Employment Cost Index (ECI), was around an annualized 5.5 percent. That’s a big number when contrasted with growth around 3 percent in 2018-2019, or even near 4 percent in the late 1990s. Is this a problem? The Federal Reserve thinks so. Here’s Fed Chair Powell last November: “demand for workers far exceeds the supply of available workers, and nominal wages have been growing at a pace well above what would be consistent with 2 percent inflation over time.”

Making the labor market worse, risking millions of people becoming unemployed, is a bad outcome, so naturally people who are opposed to it have been doing a lot of diving into the wage data. When revisions to average hourly earnings showed a surprise acceleration last November, everyone raced to explain what drove it. Everyone then raced again when those revisions were revised back down the next month.[1] It’s very odd for so much of the world’s economy to hang on a single quarterly BLS value, but everyone is naming the ECI wage number that comes out next Tuesday, January 31th at 8:30am, as central to the analysis of what’s happening to wages and inflation.[2][3]

It’s important to parse the numbers - I certainly spend too much time doing it. But it’s also useful to step back and figure out what’s actually being argued and what evidence would be convincing here. When people argue that Powell is wrong for saying current high nominal wage growth is inconsistent with 2 percent inflation, they are generally making 5 different arguments. I find stating the theory to be a useful exercise in general, but cataloging what people disagree about in these debates is important to moving the debate forward—especially if the ECI number comes in hot, or even sideways, next week.

The five arguments are:

Nominal wage growth is going to decelerate on its own.

For the time being, our high nominal wage growth is consistent with lower inflation.

The link between high nominal wage growth and inflation being self-sustaining isn’t as clear cut as the theory would say.

The higher inflation level implied by current levels of nominal wage growth is not bad, and perhaps even good.

We should manage high nominal wage growth administratively rather than through increasing unemployment.

Let’s take them in turn. But first, the background.

The problem as Powell sees it and important caveats

Why would the Federal Reserve think high nominal wages are a problem? They would say:

Demand: People spend the money they make, and as higher wages turn into higher expenditures in an economy already facing supply capacity issues we end up with too much spending chasing too few goods, which are resolved through higher prices.

Supply: There’s too few workers capable of producing what people are buying: firms, in turn, are happy to pay higher nominal wages knowing that they’ll just pass along the increases through higher prices in a period like this.

Expectations: High inflation, no matter its source, creates an expectation of future inflation; workers and businesses anticipate these future price hikes and build them into their wages and pricing decisions, perpetuating them.

The first is often called “demand-pull” (demand has pulled-up prices and wages) and the second “cost-push” inflation (costs are pushed through to prices). You can think any element here is wrong or overstated while noting that they are all independent yet self-reinforcing.

It’s worth taking the moment to understand this argument before proceeding, and many economics writers have been able to describe it with much cleaner descriptions than I can. Here is how Matthew Klein does it:

It’s not so much that higher wages push up costs for businesses that then pass price increases on to consumers, although that dynamic can be relevant for certain sectors. Instead, the bigger issue is that employment income is the largest and most reliable source of financing for consumer spending.

Or as Joseph Politano summarized it: “Critically, wages are both a major demand-push and cost-pull driver of services inflation: higher wages raise the costs for labor-intensive services like haircuts or childcare while also buoying demand for housing.” Also see Employ America here on distinctions between the first and second category.[4]

Let’s add some caveats, answering the objections you might have:

Inflation isn’t spiraling! Though this dynamic is often called a ‘wage-price spiral’ it has nothing - at all - to do with rapidly increasing hyperinflation. The question is more about persistence: if inflation stays high indefinitely or takes a very long time to come down to 2 percent.

We’ve been winning! This isn’t about the high inflation of early 2022 that has since fallen, but about the final mile of fighting inflation. Inflation has come down rapidly as things normalize; if you are looking at core CPI inflation, it’s fallen half from 6-7 percent to 3-3.5 percent in the past several months. This is the question of getting whatever inflation you are measuring, which is likely in the 2.5 to 4 percent range at this moment, to 2 percent.

Inflation was transitory! This argument is independent of the sources of inflation so far, whether they were transitory or not. It’s a forward-looking argument.

I see people arguing that wages haven’t caused our inflation so far, so what’s the deal? But Powell believes that as well, as he noted at a November press conference: “I don’t think wages are the principal story of why prices are going up. [...] I also don’t think that we see a wage–price spiral.” However, “once you see it, you’re in trouble. So we don’t want to see it. We want wages to go up—we just want them to go up at a level that’s sustainable and consistent with 2 percent inflation.”

So what are the counter-arguments? There are five I see:

(1) Nominal wage growth is going to decelerate on its own.

The argument here is that wage growth at this level is unlikely to continue, and instead reflects the special circumstances of the past two years. Wages and non-wage labor market indicators (e.g. the quit rate) have already slowed across 2022, though the rate of deceleration also slowed during the second half of the year. Key pieces of evidence here:

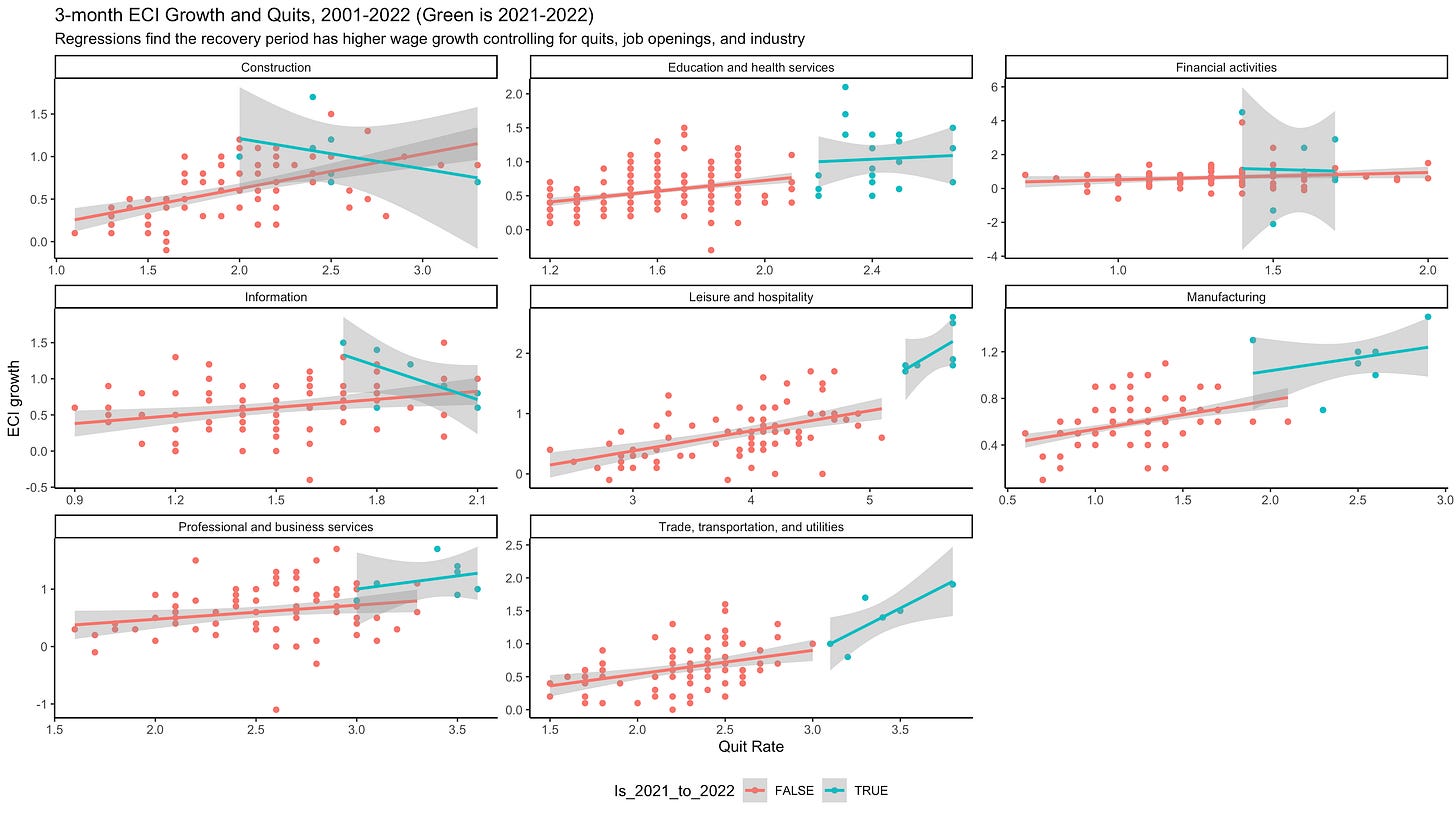

(a) Wages are far higher than what would be predicted by labor market tightness. Here’s a chart of the quits rate (what I think is the best indicator of labor market tightness) versus ECI wage growth, from 2001 to 2022. As we can see, there’s a big wedge between what quits would predict and what we got. This is even more notable at the industry level, and a dummy variable for the years 2021 and 2022 is positive on regressions.[5]

So there’s something about wages that aren’t reflected by the levels of labor market tightness. Perhaps this relationship is nonlinear in this range (Ball, Leigh, Mishra 2022); if that is the case then a slight decrease in demand would bring wages back to trend faster.

(b) Wages reflect one-time reallocation and readjustment from reopening. We know that as demand shifted from services to goods and back, there was a significant amount of shuffling of workers across places and industries. Because of nominal wage rigidities, wages aren’t falling when demand gets pulled from somewhere (Guerrieri et al 2021), which pushes both overall inflation and wages higher than they would be. But as life settles down, wages should normalize as well.

(c) Wages reflect a one-time compression of low-wage work towards the median resulting from weakened employer monopsony power. What is most surprising about this wage growth is that it’s been concentrated at the low-end of the income distribution. As Vice Chair Brainard recently flagged, “in the aggregate, the gains among lower-wage workers were more than offset by real wage declines among middle- and higher-wage workers in the context of a broader compression in the real wage distribution.”

This speaks to market power. As detailed in forthcoming work by David Autor, Arin Dube, and Annie McGrew (slides), wages are increasing not just from demand but from a weakening of employer monopsony power. Wages have increased the most among the bottom half of the income distribution, the lowest paid third of occupations, Black and hispanic workers, the youngest workers, and workers with just a high school diploma. They model how the labor supply curve has become more elastic from both additional options and extra liquidity from pandemic savings and income support. In my read, these wages reflect a necessary correction to the bad labor markets of the previous decade, a boost to productivity and overall economic health, and also something that will level out with time.

(2) Our high nominal wage growth is consistent with lower inflation.

Without detouring into equations, if productivity picks up or business profit margins compress, there’s room for inflation to come down for any given level of wage growth. So:

(a) Labor productivity is/will increase, as wage growth is concentrated among job switchers; labor market dynamism enhances productivity and dynamism even if that involves a lag. Labor productivity is notoriously difficult to measure or predict. But most of the wage gains have involved people switching jobs. Sadly, the popular coverage of job switchers we’ve seen is how they are difficult to train on short notice and slowing productivity. But the academic literature is generally optimistic on the impact of job-to-job transitions on increasing overall productivity, employment and real wages (Davis and Haltiwanger, 2014), as we expect reallocating already-employed workers to more productive and profitable enterprises increases growth and innovation.

(b) Business profit margins will decrease; the labor share will increase. Last spring I co-wrote a paper on the giant increase in firm-level corporate markups over the pandemic, and I took pains to clarify in the subsequent coverage that ‘we’ll likely see this reverse in 2022.’ As goes many of the predictions I’ve made over the past two years, the opposite happened, as corporate margins’ contribution to the price of gross value actually increased in 2022. More generally, the labor share is flat or decreasing during this time.

But there’s room for that to reverse. Vice Chair Brainard has flagged the notable “price–price spiral, whereby final prices have risen by more than the increases in input prices. The compression of these markups as supply constraints ease, inventories rise, and demand cools could contribute to disinflationary pressures.” More generally, researchers such as Josh Bivens of EPI emphasize that labor share increases through a business cycle, and now is a time in which we can see that happen.

(3) The link between high nominal wage growth and inflation isn’t as clear cut as the theory would say.

What the Federal Reserve worries about involves a system of self-reinforcing patterns and loops. But it’s worthwhile to pick at these.

(a) Expectations remain anchored. Insomuch as one important mechanism of high wage growth and inflation perpetuating each other is people expecting inflation to continue at the current high level, we don’t see that reflected in the data. Without detouring too far, expectations surveys are sending good signals.

(b) It’s not clear workers are going to bargain increases in inflation into higher wage increases. There was a good piece in the New York Times arguing that we simply don’t know if, given inflation, workers are going to bargain for higher wages to compensate for it. Without, say, cost-of-living adjustments built into union contracts, the mechanism isn’t as obvious. I’ve been watching the new Indeed Wage Tracker (worth checking out!) and noting that high-wage earners are also seeing their wage growth decelerate; if workers were going to respond to higher than expected inflation by bargaining for higher wages, I'd expect to see it most among higher-wage earners, whose wages have most lagged inflation and presumably have some room to bargain. So far, we aren’t seeing that happen.

(c) There are multiple Phillips Curves Behaving Oddly This Decade. The accelerationist Phillips Curve one learns in an undergraduate textbook says that for inflation to come down, unemployment must go up. But, often to the cringe of economists, the New Keynesian Phillips Curve one learns in graduate school finds that inflation decreasing can be consistent with unemployment staying the same or even an economic boom. Expectations play a central role.

Instead of getting lost in theory, here’s how I’m approaching it: during the Great Recession there was a mirror debate - how was inflation remaining so high, so close to target, given that the output gap was so large? This question of the “missing disinflation” of the 2010s also involved interrogating various Phillips Curves, and they found (at least) two answers: expectations kept things anchored (Coibion and Gorodnichenko, 2015), and the Phillips Curve had a nonlinear structure (Trabandt and Linde, 2019). If either or both are in play now, it’s much easier to see us being able to bring down inflation with little cost to GDP and employment. We just don’t know; but as economists can’t explain why the Great Recession didn’t see outright deflation, maybe someday they won’t be able to explain why inflation came down so quickly now.

In addition to these arguments against the premise, here’s two other arguments out there that accept it but go in different directions than trying to lower demand via weakening the labor market.

(4) The higher inflation level implied by current levels of nominal wage growth is not bad, and perhaps even good.

There are tradeoffs to fighting inflation. What if instead of focusing on bringing inflation down to 2 percent exactly, we accept it may float in the 2 to 3 percent range for some time to preserve a fantastic labor market? It’s worth splitting out two arguments here.

(a) The low cost of inflation contrasted with the high cost of unemployment. It’s difficult to argue about tradeoffs when inflation was in the 6-8 percent range. But as inflation lands in the 2-3 percent range, it’s harder to just focus on inflation as the problem. Especially with the high cost of unemployment, which has two dimensions: the long costs on the unemployed themselves, and, as my friends at Employ America document, the likelihood that starting to increase unemployment causes a cascade that increases unemployment far higher than originally anticipated.

(b) Higher inflation provides more flexibility for business cycle management. As Justin Bloesch documents in a recent Roosevelt Institute paper, if you were designing an inflation targeting regime there’s really a good reason to have a larger range between 2 percent and 3.5 percent, rather than a single point target. Many people made arguments during the Great Recession for an inflation target at 3 percent or above; Bloesch notes that the recent inflation actually bolsters those cases. Many who made this case during the Great Recession are continuing it now, see, for instance, Olivier Blanchard and Joe Gagnon.

(5) We should manage high nominal wage growth administratively rather than through increasing unemployment.

There was a bit of flutter in economic circles when Olivier Blanchard had a twitter thread arguing that we should understand inflation as not about money, or spending, but as a distributional, coordination problem between workers and firms - one where the ideal but unlikely solution would be “a negotiation between workers, firms, and the state, in which the outcome is achieved without triggering inflation and requiring a painful slowdown.” Post-Keynesians were ecstatic; some, like Adam Tooze, found it suspect that intellectual energy was going into how inflation is a problem of workers and firms fighting at a moment the Fed needs external justification to start a recession while inflation has fallen in half over the past three months.

But either way, there’s a set of arguments that high wages are going to be a driver of inflation but we should instead handle this administratively. A full dive here is outside the scope of this post, but there’s two versions:

(b) Engage in incomes policy. To get a list the last time this was debated in mainstream circles, we can look to the 1976 10th edition of Paul Samuelson’s Economics, which added a chapter on ongoing stagflation. Samuelson defines “incomes policy” as a way to “fight inflation in a modern mixed economy other than to engineer deliberate unemployment and a contrived slowdown to cool off the economy.” He lists “government guideposts (voluntary or quasi-voluntary), direct wage-price controls, centralized collective bargaining, stop-go driving of the economy to cool it down, manpower and retraining programs” as among the tools historically deployed here (though remains skeptical they can work).

(b) Institute price and wage controls. We’ve seen calls for price control throughout the recovery, often modeled on World War II, but proponents have generally not discussed the wage controls that go hand-in-hand with them. But as people discuss targeted price controls as part of the toolkit of managing high demand, wage controls will also likely follow.

So, right now, the dovish case is that wages will normalize as the economy continues to reopen, there’s margins that can adjust to lower inflation as well, the evidence for expectations currently becoming embedded is weak, and we’re now in the range where the costs of a recession far outweigh the last mile of fighting inflation, especially with so much tightening that has yet to be felt. The case for patience is strong going into 2023.

[1] Claudia Sahm’s Stay-At-Home Macro featured an in-depth analysis by former Fed official Riccardo Trezzi of the caliber Jay Powell himself likely got. Though note even while Trezzi argues “we are also unsure that there are convincing signs of [wage] re-acceleration” he also concludes “Wage and possibly total compensation growth remains above the level consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target.”

[2] Governor Waller: “Wages, as I indicated earlier, are another stream of data that I will be watching for evidence of continued progress to help ease overall inflation. [...] The employment cost index for December won't be out until the end of this month.”

Larry Summers: “The most important day of this month will be the last day of the month when the employment cost index comes out. That's a number they'll be studying very, very closely. I'll certainly be up early that morning to get that number.”

[3] If you are interested in why there’s so much focus on this number, this is a good overview of ECI wages. The way it is constructed varies less over the business cycle than other measures because, among other reasons, “the ECI holds constant the distribution of employment across industries and across occupations, it is not influenced by the differing cyclicality of employment across jobs and sectors.”

[4] Abba Lerner used the phrasing “buyers’ inflation” and “sellers’ inflation” to refer to demand-pull and cost-push, respectively, and I find that a useful point in explanation. Lerner: “While buyers' inflation is caused by too much spending, i.e., by buyers trying to buy more goods than are available and thereby bidding up prices, sellers' inflation is caused by sellers raising prices even in the face of a deficiency of spending.”

[5] Regressions with industry-category data (below), using industry controls, show a dummy variable for 2021-2022 is always positive and statistically significant.

Does no one believe in maximum employment anymore? What if the unemployment rate keeps falling? Will these arguments change?