Miran’s Case for Cuts: A Reminder of Why Independence is Essential

Stephen Miran's recent speech highlights not just a debate over r*, but the deeper risks of allowing White House talking points to shape monetary policy.

Now that it’s under unprecedented political assault, I keep finding new arguments for central bank independence. There are the classic ones from the economics profession, summarized by an all-star bipartisan team of former Federal Reserve and White House officials here. But I’m discovering other reasons to keep central bank policy from being dictated by the Executive Branch.

Over the summer I argued that the independence of the Federal Reserve allows officials to have frank discussions of the data, where the White House is always playing some communications role. The Fed can have a serious discussion on whether the labor market is slowing and we’re losing jobs, while the White House keeps on talking about how well everything is going. The Fed doesn’t get subsumed into comms talking points.

Another thing I just realized this past week was that genuine outsider takes on the FOMC can be examined as such, without having to worry that they are carrying water for the White House. The Fed can be subject to groupthink, so having a few people to shake up the consensus can be welcome, so long as they are independent. If they are not, it’s hard to determine what’s good faith pressure on conventional wisdom, and what’s ad hoc justification for the President’s priorities.

Is r* at zero percent?

Take Stephen Miran, on leave from his job as President Trump’s chief economist at the Council of Economic Advisers to join the FOMC. Many have worried about the obvious conflict of interest in his simultaneously holding one of the most senior White House roles while voting on the committee. And he just gave a speech, Nonmonetary Forces and Appropriate Monetary Policy, arguing for significant rate cuts based on the idea that President Trump’s policies have quickly reduced the neutral rate of interest (hence r*) to zero percent. Miran:

I get a new real r* that is 1 to 1.2 percentage points lower, or near zero. [...] Leaving short-term interest rates roughly 2 percentage points too tight risks unnecessary layoffs and higher unemployment.

It’s worth reading and discussing. As Claudia Sahm notes, there is nothing in the aggregate data to suggest that rates are that restrictive. Just so you don’t think this is all lib stuff, Wall Street isn’t buying it. JPMorgan’s Michael Feroli wrote “We find some of his arguments questionable, others incomplete and almost none persuasive,” and, as Molly Smith reports at Bloomberg, that’s a pretty consensus take.

But there’s a bigger problem that goes to central bank independence. There’s no polite way to say this so let’s just do it: it is difficult for all of us to determine if this speech is his genuine outside-the-box thought, or an attempt to shoehorn in what the President (his boss, whom he still serves at the pleasure of even while on leave) wants to see. Without true independence, this worry will always be with us.

Thought Exercise - Do This Backwards

To show the conflict, I want to motivate this with a quick thought exercise. Let’s say you work for the President, like Miran does, and have been ordered to come up with a justification for what Donald Trump wants. Over the summer President Trump told Maria Bartiromo in an interview, in a response to a question about the federal debt, that “when you get somebody into the Fed who’s going to be able to lower the rates, we should be at 1% or 2%.” How could you justify a 2 percent rate on solid economic grounds?

Now you can’t say the obvious and base the case for rate cuts on a weakening economy. Miran doesn’t mention the slowing labor market at all in his speech. Whether it’s a “somewhat softer labor market” (Powell) or “a labor market on the edge” (Waller), the new debate for cuts is predicated on a bad labor market. However you just saw someone get ended simply for showing that job growth was slowing, like a movie where the villain just knocks off advisers for saying factual things. So you aren’t going to say that.

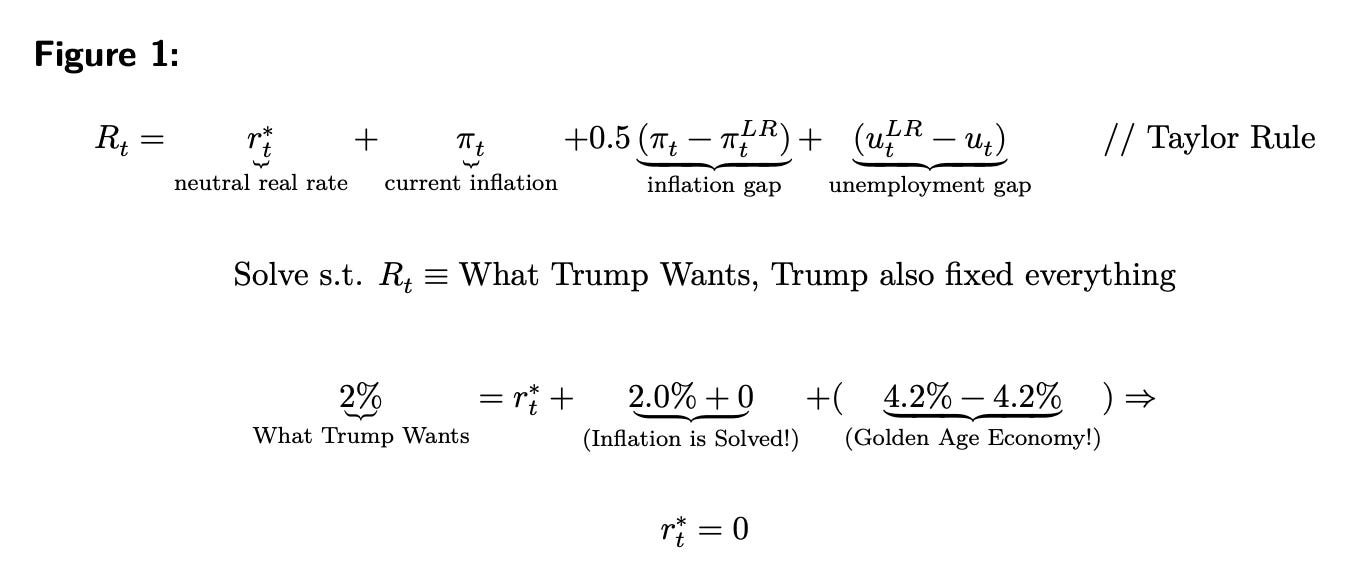

There are other constraints. You sensibly don’t want to say inflation is below target, that doesn’t seem credible. And you don’t want to propose a brand new framework, explicitly declaring fiscal dominance, because you don’t want to freak people out. But you also need some math, ideally in the Taylor Rule framework.

The only thing to do to meet the President’s demand is to argue about r*. It’s the only free variable. Specifically, with some algebra in Figure 1 above, the only thing you can do is to find a way to argue it is zero percent. Trying to discuss an unobservable and theoretically debated idea like r* is going to involve a lot of hand-waving and balanced guesswork. But that this conclusion so naturally fits what the administration wants should give us pause.

Reversing Course

Now, of course, people with outside-the-consensus arguments tend to be consistent about them. So has Miran been arguing r* was quite low for a while? No. Many (e.g. Jonathan Levin) are flagging that Miran is contradicting his own previous arguments, as he had spent 2024 arguing that r* had increased significantly. See, for instance, his March 2024 Barron’s article, The Fed Is Facing a Changed World. The Case Against Cuts, with Sander Gerber.

There are five reasons he gives for why r* had been increasing. We’ll discuss two, immigration and the budget, in a minute. But three are quite obviously still with us and have likely accelerated. It’s worth quoting at length, my bold:

[First] Household debt fell from about 100% to 75% of gross domestic product between 2010 and 2019, but has been stable since. [Second] Wars and the proliferation of sanctions and tariffs incentivize firms to invest in supply-chain resilience over efficiency, which requires capital expenditures and boosts neutral. [Third] Finally, while software investment last decade was capital-light and suppressed rates, the 2020s seem to be more demanding on hardware for national security purposes and new AI technologies.

All three are still in play and have accelerated. Household debt has continued to fall in 2025, trade wars are far more vicious than one would have predicted in 2024, and the economy is running even more on capital-intensive AI investments.

And to back up, Miran wasn’t alone in arguing this in 2024. The FOMC and financial markets recently moved their estimate of r*. This is a whole other giant discussion, but in the same way people argued r* was down in the 2010s, they argue it is creeping back up now. But those are debates about big ongoing forces, like an aging population or productivity growth. Will those old secular stagnation forces still drive fundamentals (e.g. Minneapolis Fed 2024), or are they already burning out (SF Fed, 2025)? It is not a debate centered on administration talking points about The One Big Beautiful Bill.

The Actual Macro Impact of Deportations

But Miran does bring up immigration and budgets as reasons to drop r*. Miran makes two arguments about why a slowdown in immigration and deportations should reduce r*.

“it is plausible to me that 2 million illegal immigrants will have exited the country by year-end,” and the lower population growth slows r*.

Following Saiz (2003), a case study of the Mariel boatlift, Miran argues that removing immigrants will lower rents, a disinflationary impulse capable of getting inflation back to target.

The first is likely an incorrect overstatement based on best estimates, a misreading of the BLS data, see this important general post from Jed Kolko and this thread by Stan Veuger.

The second misses a whole literature that has evolved far later than Saiz (2003) on immigration and inflation. First, in a broad level, higher immigration is associated with lower price level for services, especially immigration-intensive ones (e.g. Cortes 2008). Given the strong remaining impulse in non-housing services this can’t simply be waived away.

This channel is particularly important when it comes to rentals and housing construction, as immigrants disproportionately work in construction. Using the rollout of ICE’s Secure Communities [SC] program, which deported 300,000 people, as an instrument, Howard, Wang, and Zhang 2024 find:

(i) when undocumented workers are deported, domestic labor only partially fills vacated construction jobs; and an apparent complementarity between immigrant and domestic labor leads to net job losses for US-born workers, (ii) residential construction output is highly sensitive to these declines in labor supply, (iii) the resultant reduction in homebuilding leads to higher home prices, with demand-driven declines in prices being small and highly transient. [...] “Three years after SC rollout, the average county of approximately 500,000 residents has foregone the equivalent of an entire year’s worth of additional residential construction.”

As decades of complementarities of immigration research would predict, other studies found SC reducing immigrant workers “also decreased the employment and hourly wages of US-born individuals” (East et al 2023), something relevant to what’s coming now. Other studies, like that of the Mexico Peso Crisis (Monras, 2020), bear this out.

More generally, the idea that the macroeconomic effect of deporting 2 million people will only show up in lower rents strikes me as implausible, especially after a period with big labor market convulsions. Reasonable estimates of deportations have a drop of 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points in 2025 (Edelberg, Veuger and Watson 2025), and that’s before we get to any new bottlenecks forming in specific labor-intensive industries.

I do find it funny that after a long period of having to get conservatives to think that immigrants don’t just take jobs, they also buy things and create jobs, we now have a conservative analysis where immigrants just buy things like housing but don’t actually take any jobs making things. General equilibrium is hard from both angles.

Admin Talking Points in the FOMC

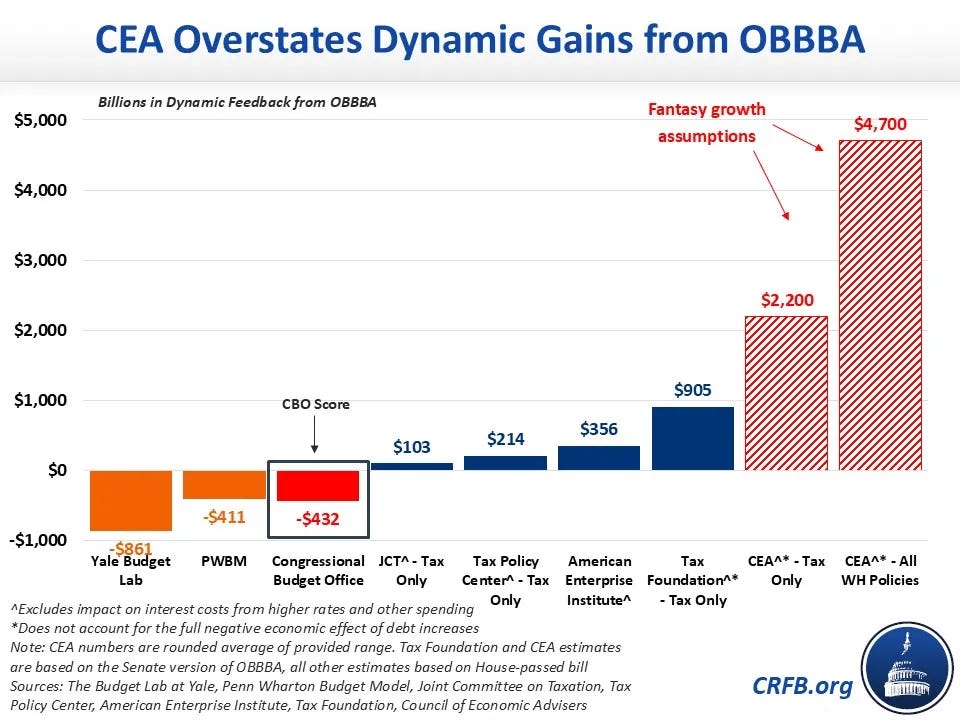

I was interested in whether or not the absurd estimates coming out of Trump’s budget process or CEA would show up in the Survey of Economic Projections. (You can read Jared Bernstein on those estimates here.) They weren’t reflected in real GDP projections for the next few years, but they apparently did in the large number of cuts reflected in the dot plot, and here in the argument now.

I find this to be a conflict and a compromise of central bank independence. The President’s mid-budget review and associated CEA materials are a marketing gimmick, a forecast so outside conventional analysis we should understand it as just a justification for the White House to say they are meeting the deficit reduction metrics they promised. There’s a couple different threads here, but to give a sense of how much of an outlier the CEA is, see this graphic from CRFB:

But where to start on the idea that Trump’s tariffs, tax law, and deficit impact are driving r* to zero? The tariff revenue may not be legal, the Supreme Court will take that up in arguments that conservative legal analysts say may be difficult for the Court to simply ignore. It’s true that OBBB reduces deficits on a current policy baseline, which is relevant for the fiscal impulse, but the numbers for OBBB itself assumes that tax cuts end at certain deadlines.

The best analysis I’ve seen says that the tariffs and tax cuts roughly balance each other out through 2026, the time the FOMC needs to be thinking about; most of the deficit reduction is backloaded in OBBB. Miran assumes the loans and loan guarantees from other countries are actually going to happen at the scale promised. I assume that never happens but even if you do, we aren’t sure of what it actually looks like enough to drive monetary policy. There’s a reason financial markets don’t take the President’s own talking points for granted, and the FOMC shouldn’t either.

I enjoy reading outside-of-conventional wisdom on macroeconomics. Most financial sector people do, it’s why there’s such a flourishing newsletter network. And I enjoyed reading and reflecting on this speech. I just wish I had the confidence it was coming from a place of independence. While Miran’s boss no doubt likes the conclusion, I’m not sure everyday people will enjoy the consequences.

Well, given that there is an unequivocal track record of outlandish lies regarding all areas of government and civilian endeavors from this administration, it seems relatively easy for me to believe that Miran is a sniveling sycophant blinded by the bulging buttocks of his dear leader. Nonetheless, Mike, your contributions are invaluable and I hope you don't ever consider quitting Rorty Bomb!