We Just Can't Quit Job Openings (and Whether Various Unemployment Measures are Moving at a Commensurable Rate Alongside Them)

A reply to Jason Furman and Wilson Powell III on their recent look at job openings and employment flows data.

“One of the perversities of this recession is that as the unemployment rate has risen, the job vacancy rate has risen, too.” No, that’s not from 2021. That’s David Brooks’s New York Times opinion column from September 9th, 2010, setting the centrist wisdom that an increase in job openings (as opposed to cascading deleveraging and millions of foreclosures) was the central disaster of the Great Recession. This sent many Obama-era economists scrambling to dig into the DMP model, the Beveridge Curve, and other obscure search theory things everyone forgets about during graduate school.

But that was then. Brooks is now loving it and joining in on the fun of job openings. In last week’s well-titled The American Renaissance Has Begun, he noted that “Between April 2020 and March 2021, the number of unemployed people per opening plummeted to 1.2 from 5.” And this time that’s awesome: “power has begun shifting from employers to workers” and that “Workers are in the driver’s seat, for now, and they know it.” The moment has “cleared the way for an economic boom.” “Economic boom” - that’s a good phrase.

Yet we still can’t quit job openings and the failure of some piece of unemployment data to move fast enough alongside them. Jason Furman and Wilson Powell III have new research at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, US workers are quitting jobs at historic rates, and many unemployed are not coming back despite record job openings, that argues (1) the relationship between job openings and unemployment to employment transitions has broken down, and (2) this is evidence of a significant decline in labor supply and a sign that job growth should be much higher. This is a good opportunity to dive deeper into a series of arguments around the high level of job openings which have been appearing in recent months.

I’m skeptical of these kinds of arguments for the following reasons.

1: Not in the Labor Force. This recession is unique in that so many more people who left employment moved not into unemployment but out of the labor force. These workers who have left the labor force are understood by policymakers as part of the unemployment rate (e.g. Secretary Yellen and Chair Powell’s cited unemployment rate), even if they aren’t conventionally counted as such, and that full employment will require getting us to the pre-crisis age-adjusted labor force participation rate.

So when we look at this graphic from Furman/Powell III, which shows transitions from U to E as a percent of U having declined in the pandemic and notably flatlined in 2021:

We should be including those who left the labor force during the pandemic among the unemployed (the denominator) as well taking all those who are not in the labor force who find jobs and including them as part of the job finding rate (the numerator). Let’s make that graphic with the transition from NL to E added to the job finding rate and “marginally attached to the labor force” (which drives the U-5 unemployment rate) added to the denominator:

Here we see, instead of flatlining, the rate of people finding jobs is increasing through 2021, and every indication that it will continue to increase.

One can quibble about what exactly I added; there’s no obvious quick way to control for the decline in labor force participation following a recession running backwards 30 years, as what should be happening to LFP trends during recent recessions is a major debate within macroeconomics. (Roosevelt has forthcoming work on this point soon.) Marginally attached workers are at least a consistent baseline to view across different recent business cycles.

Two: Changing Job Openings. I’m not sure we can look at job openings as a rate that exists independently across recent business cycles. Advancements in technology have likely made it cheaper to both create and maintain job openings in recent decades.

Let’s do a regression with job openings as our dependent variable and just looking at unemployment during the period of the Great Recession, from 2008 to 2019, and then compare that line with the actual job openings rate before, during, and after:

It fits well during the Great Recession, until the end at least. Yet, as we can see, there was an increase in the number of job openings predicted by unemployment during the Great Recession (given that the estimate predicted much higher job openings previous to the Great Recession), consistent with technology reducing the cost of creating and maintaining job openings during the 2010s. But what’s more interesting for me is the complete lack of collapse of job openings during the pandemic. We should have seen job openings fall a significant amount, yet they basically stayed the same, and then increased more.

This isn’t to say there aren’t a lot of job openings. There are. The question here is whether or not job openings provide an independent measure of the labor market consistently across the last several business cycles. I am skeptical that they do.

Before moving on from these two points, I’ll also say that research looking at the question of flows and job openings during the tail end of the Great Recession also brought up these points. Take the Brookings paper How Tight is the U.S. Labor Market? by Katharine Abraham, John Haltiwanger, and Lea Rendell from March 18th, 2020. (Getting in there right before the pandemic changed the nature of that question!) They also look to an expanded definition of unemployment and job searchers, as well as a weaker intensity of employer recruitment (consistent with a job opening becoming cheaper to open and maintain), to see that these relationships were breaking down during the tail end of the 2010s. You can see that in their summary graphic here:

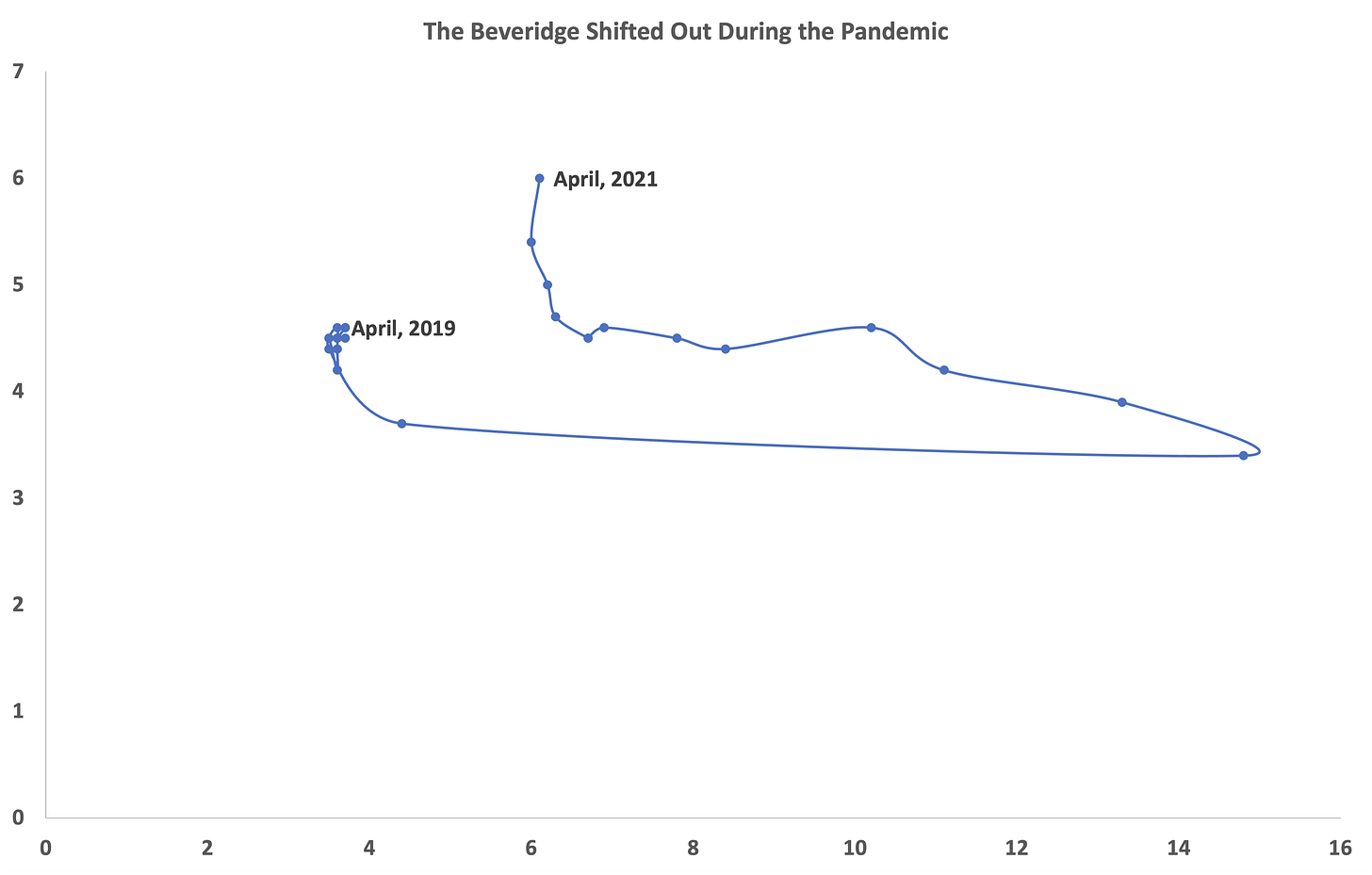

Three: The Beveridge Curves Shifts Out During Recessions and Recoveries. Back to the 2010 vintage David Brooks question. All of these arguments in some way replicate the debate about Lord Beveridge’s Curve, or the relationship between the number of job openings and job vacancies. And sure enough in 2021 we see that, for a level of unemployment, job openings have increased, implying a deterioration in the economy’s ability to match jobs. Or, the Beveridge Curve has shifted out. Here’s what that looks like in this pandemic:

So has this happened before? Yes. Has this happened in every recession we have data for? Also yes. From Peter Diamond and Aysegul Sahin in Shifts in the Beveridge Curve, here’s what it looks like in every recovery from a recession since 1954:

There’s always a shift out in the Beveridge Curve during a recovery. The reasons why are an interesting debate, and perhaps this one is more shifted than others. But this is a common occurrence; it would be odd if it wasn’t happening. That secondary measures - like transitions from unemployment to employment - are also shifting doesn’t necessarily tell us much.

Four: What Are Transition Rates Telling Us? I’m also a little uncertain why we’d shift the debate from unemployment rates to unemployment flow rates. Like many turnover measures of “market dynamism” I’m a little uncertain why we care about them in a vacuum. If everyone quit their job at the end of the day and then is rehired in the morning, but nothing else changed, would we care that the true value of the U to E rate was in the thousands? Probably not. We care about unemployment to vacancy ratios because of arguments derived from the DMP search model of labor markets; but I’m not sure if our concern extends for the same reasons to transition rates among those unemployed.

This ambiguity hangs over many discussions over longer-term declining trends in these rates, something that does worry me for what it says about market power. But even then, it’s not always clear. To take a random example, the 2015 CEA’s Annual Report noted: “It is less clear, however, how the long-run decline [in labor market dynamism] should be viewed given that it has the potential for both positive aspects in terms of job stability and better matches, and negative aspects in terms of potentially less effective reallocation of labor to its highest productivity uses.” Economist Thorsten Drautzburg had an informative primer on this question from a different direction, Just How Important Are New Businesses?, at the Philadelphia Fed on this.

In the short-term remember these transition rates are not representative of the labor market as a whole, but tend to reflect high turnover in specific industries. We know from Minimum Wage Shocks, Employment Flows, and Labor Market Frictions, by Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester, and Michael Reich, that higher “minimum wages have a sizable negative effect on employment flow.” This is reflective of the monopsony power employers have over low-wage jobs, and its reduction is a good thing. Insomuch as the recovery is creating a higher and binding minimum wage across industries (a sense you get from reporting calls for major service-employing businesses) that would reduce turnover, and be great. What relationship that has to quit rates is uncertain, but could be consistent with a major immediate boost to quits. This is speculative, but it goes to show that it’s unclear what the problem even is yet.

All things equal, I still think it’s worth letting the economy continue its recovery, without undue panic about anything we see. There are many signs the boom will get even better with the proper management and ownership.