Inflation Came Down and Everyone Was Right

Inflation has been falling over the past year, yet, inconsistent with 'mainstream macro,' unemployment has not increased. What are some of the reasons this could happen?

Let’s not overstate one good month for inflation. But the CPI for June, 2023 was a good month. Here’s my overview on Twitter; a lot of things we had been hoping to see showed up at the same time. There’s still a long slog to go.1 PCE is going to be more stubborn. Housing is a smaller component there so it’ll benefit less from the disinflation we’re going to see; PCE’s measure of overall health care spending has been hotter too.

But we couldn’t have some progress without everyone rushing to declare who was right and who was wrong. Noah Smith has a column where he grades “schools of thought” where he gives “mainstream macro” the best grade at an A-. I don’t find “mainstream macro” to be a useful term, given it can range from monetarists to Old New Keynesians to DSGE rational expectations modelers; from those who think expectations are backwards-looking, forwards-looking, or some Frankenstein monster of in-between; it also ranges from economists killing time on Twitter to top academic journals. It could be anything.

Noah simplifies and says it represents the idea that “when you raise interest rates and/or reduce budget deficits, inflation and economic activity go down.” And I think that’s a useful definition, the kind taught in intermediate textbooks, where if demand is too high, inflation can’t come down without unemployment going up. But economic activity didn’t go down. Unemployment hasn’t increased.2 This is an open question right now: why has inflation fallen without any increase in unemployment?

To answer this it’s worth looking at two of the workhorse models of inflation and the variables that could have accomplished this. Maybe we can have less “teams” in 2023 and more “arrays of variables.” On the first pass, we can give everyone an A: all these variables could have played some role. Or, at least, everyone is going to have a legitimate claim for being correct, so don’t expect any clean answers on who was right in the near future.

The Accelerationist Phillips Curve

This is what you encounter in an advanced undergraduate class. Inflation comes from backwards-looking expected inflation, an output gap of demand relative to supply, and supply shocks. It’s a fun algebra exercise to move the variables around to show that, holding expectations and supply shocks constant, the only way for inflation to fall is for unemployment to increase. But unemployment didn’t increase. So what variables could explain the fall in inflation?

ν - Supply Shock. If inflation is the result of a series of supply shocks, between paused production during the pandemic, to fragile supply chains, to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, then we’d see inflation increase and then decrease as things normalize, without unemployment necessarily going up.

Adam Shapiro of the SF Fed has documented a rise in inflation from supply-shocks (measures as items that saw both quantities decrease as prices increased) that has since declined. The case against this is that inflation is much broader than the goods impacted and that inflation continued on even after many of the supply chain problems are behind us. Though note in models of supply shocks, inflation can be broader and more persistent than that.3

α - Nonlinear Phillips Curve Slope. α in the equation above is generally treated as a single number, so the Phillips Curve is a straight line. But what if the Phillips Curve is flat through a large range and then suddenly goes vertical? If this was true, you could get a large decrease in inflation from just a small decrease in output. This could also help explain why forecasters who anticipated inflation from high demand all missed the level of inflation.

θ, u* - Attention-Based Expectations, Time-Varying NAIRU. I haven’t seen these discussed much, but could be something people argue. Perhaps people pay a lot of attention to inflation above a threshold, and as inflation moved out of that range so did people reinforcing it. I’m generally skeptical of time-varying NAIRU/potential output arguments, but given how crazy the last two years have been perhaps some equivalent was in play - we could still produce as much, it just needed a minute to catch up.

This gets us pretty far. And most of the public-facing debates have been around the first two variables here. But it’s worth going one layer deeper, to understand what the academics will be fighting about.

The New Keynesian Phillips Curve

In a world where you are forced to learn recursive methods and dynamic programming as part of your qualifying exam before you can work on the stuff you want there are nominal rigidities to firms being able to change prices, you can end up with this.

Here inflation is the result of expected inflation in the future, market imperfections in the form of nominal rigidities in price-setting, and markups over real marginal costs. There’s two things that differentiate it from above. The first is that we’re seeing inflation coming out of the decision-making of individual firms considering the future costs they are facing, where the other model is based in contemporary aggregates. The second is more important - inflation is forward and not backwards looking.

So three things can bring down inflation here.

π (t+1): Future Expectations Held/Fell. In the other model inflation is based on past inflation, which is a function of unemployment. So to break inflation you have to change unemployment. In this, inflation is based on the future, which is just vibes. If you can change what people expect to happen, you can change inflation without changing the business cycle. After a brief hiccup, Chair Powell was able to keep everyone’s expectations of where inflation would land in place - did you see the press conferences? It was clearly a regime shift.

From my outside observation, this conclusion has split the academic macroeconomics field in half. Macroeconomists who came up with it clearly do not like it and believe it fits the data very poorly. Newer economists seem to take it for granted as part of their toolkit?4 To see this argument about anchored expectations here, read this by Reifschneider and Wilcox.

Nominal Rigidities Cleared. I’m going to cheat a bit and put in the fact that we saw large shifts in spending between goods and services during the recovery into this section. When spending shifts out of a sector wages and prices don’t fall in response, so big shifts will mechanically increase inflation. The modeling of this by Guerrieri, et al presented at Jackson Hole in 2021 was part of the transitory argument then, and maybe it’s clearing now.

Margin Increases Stopped. Inflation is firms raising their markups; they are doing that less now. It is funny how ‘greedflation,’ with its staggered price setting and firms testing margins, reads as clearly within the New Keynesian mental framework. But whether firms were raising margins as competition constraints fell (Weber/Wasner) or because they rationally anticipated a wave of marginal cost increases in the future (Kansas City Fed) that wave has slowed.5

Maybe it’s something else entirely. But, as much as we’ll all breath a major sigh of relief if inflation continues to fall and want to put it behind us, we’ll need to figure out what actually happened.

There were several partial victory pieces written with Larry Summers’s 2022 comments about unemployment needing to go up for inflation to fall as the foil (Eric Levitz, Adam Ozimek). But in his July 2022 interview with Jordan Weissmann, Summers “assumes the Fed will have to lower inflation by 2.5 percentage points in order to reach its official target of 2 percent annual price growth.” Or that, underneath all the supply shocks that had inflation sky-high, PCE inflation was around 4.5 percent. So far, in 2023, core PCE is an annualized 4.6 percent.

Noah’s piece anticipates this by noting “the main criticism that people are lobbing at mainstream macro here is that this victory wasn’t costly enough. Unemployment didn’t rise significantly” but that “this seems like an odd criticism” given we should celebrate the lower cost as a great thing.

There’s two problems with this. The extra disinflation isn’t just a nice bonus but the actual methodological problem we need to figure out. When Sargent argued that big inflations stop with a speed inconsistent with backwards-looking expectations formation, he didn’t follow up and say “and that makes the Phillips Curve even more awesome, you get all this free disinflation, it’s all gravy.” It was a challenge that had to be answered.

Second is that as the Fed normalized rates there’s been the question of whether they should raise them to actively try and create a recession. If the policy guidance has that level of unnecessary cost in its recommendations we need to figure out why.

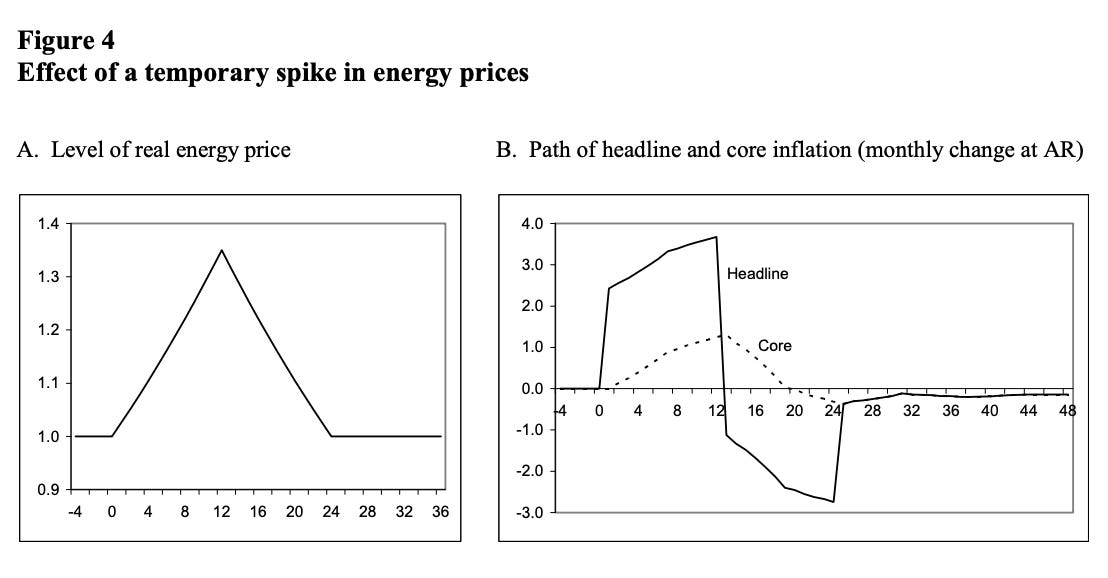

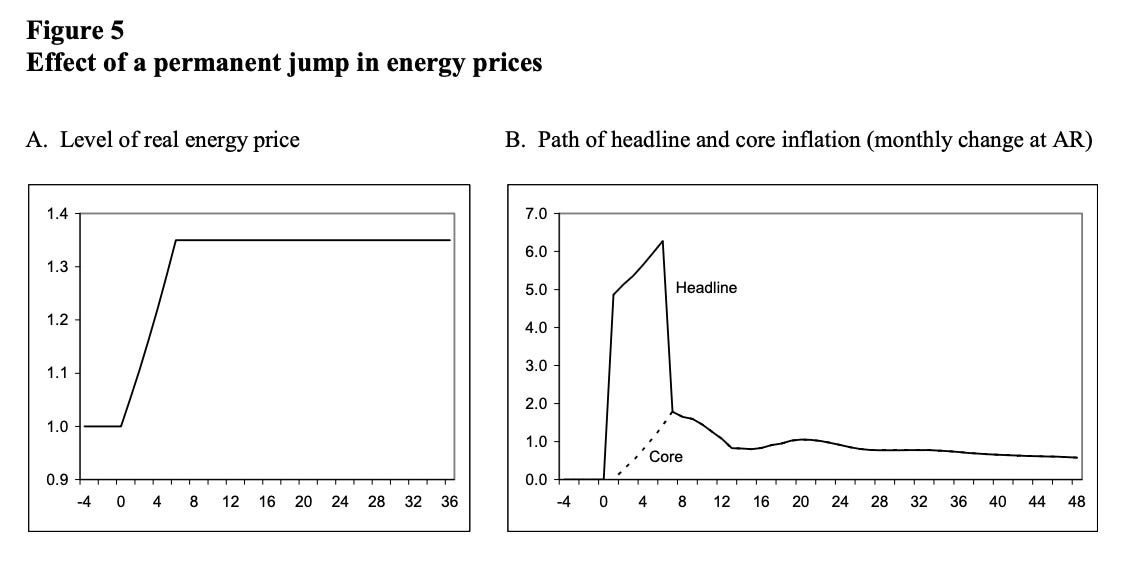

From Blinder and Rudd’s The Supply-Shock Explanation of the Great Stagflation Revisited, here’s how they model an energy supply shock:

In his 2008 “The State of Macro” review, Olivier Blanchard describes the “enormous progress and substantial convergence” in the field, while also noting that the New Keynesian Phillips Curve is “patently false” and “implies a purely forward looking behavior of inflation, which again appears strongly at odds with the data.” If that’s progress…..

Meanwhile this recent Hazell, Herreno, Nakamura, and Steinsson paper, by the new generation of superstar macroeconomists, just moves right along, concluding “that the sharp drop in core inflation in the early 1980s was mostly due to shifting expectations about long-run monetary policy as opposed to a steep Phillips curve, and the greater stability of inflation between 1990 and 2020 is mostly due to long-run inflation expectations becoming more firmly anchored.”

There was some debate over whether or not the Kansas City Fed paper vindicated “greedflation” (see Matt Bruenig); from Kansas City’s POV the markup increases are to keep them consistent across time rather than opportunism. Since nobody can measure marginal costs - and no, labor share doesn’t count - everyone can get a A.

It is funny to see the economics profession say things like “don’t model that firms can attempt to expand market power in a global crisis, that’s insane; model reasonable things like firms post a price and they have to sell an indefinite amount at that price for what could be a stochastically extensive amount of time.”

As long as "inflation" is only considered an attribute of commodities and not of assets (except housing) how can any theory of monetary price inflation make sense?

How did the Phillips Curve become a relationship between all-price inflation when it originally only demonstrated a relationship between wage inflation and unemployment--and explicitly exempted inflation caused by externalities like energy?

Why do economists often rely upon inherently unmeasurable variables such as "expectations (of inflation)," velocity of circulation (of money)", "marginal cost" (of production)"? Is it their utility for propping up other, measurable variables that wouldn't otherwise conform to theory?: "Feather pillows to catch failing theories."

I appreciate your skepticism!

It's not rocket science. Spending went up, so Balance went up. NAIRU went up cuz it's correlated with balance. When unemployment fell below NAIRU, inflation rose. Big deficits ended, Balance went down and NAIRU went back down. Inflation begins to fall. See Fig 3 in my current post for details.