People Really Like Quitting Manufacturing Jobs in a Hot Labor Market

Manufacturing jobs had among the highest increases in people quitting their jobs during 2022-2023, a period with some income security and plentiful job offers.

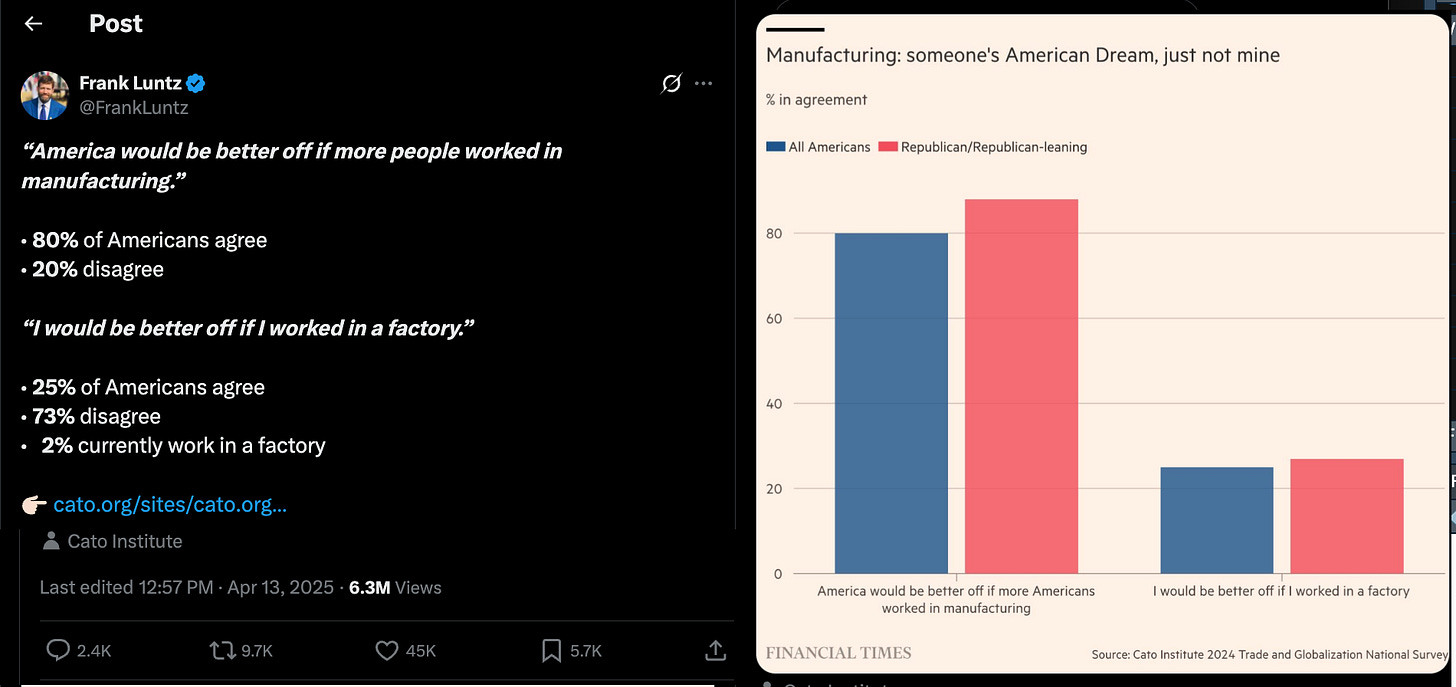

There was an online back and forth about polling from the Cato Institute that found 80 percent of people agree “America would be better off if more people worked in manufacturing,” but only 25 percent agree “I would be better off if I worked in a factory.”

Frank Luntz tweeted it out, Tej Parikh wrote about it at the Financial Times (“Nostalgia for manufacturing will make the US poorer”), as did Oren Cass of American Compass and Scott Winship at AEI at their sites. It was around, you might have seen it.

Related, Jordan Schneider shared this tweet from a 2018 Bob Woodward book1, where National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn explains JOLTS data to President Trump:

As written, Cohn’s statement is incorrect: most industries have higher quit rates than manufacturing, notably leisure and hospitality workers (who have the highest).2 But I am curious about the recent JOLTS data and how I would present this to President Trump.

This issue has important stakes. One reason we’re blowing up the international order and risking stagflation is to bring back manufacturing jobs. Or at least I think that’s part of the reason? The exact justifications are vague, though I think this has a longer conservative pedigree worth exploring in a footnote.3

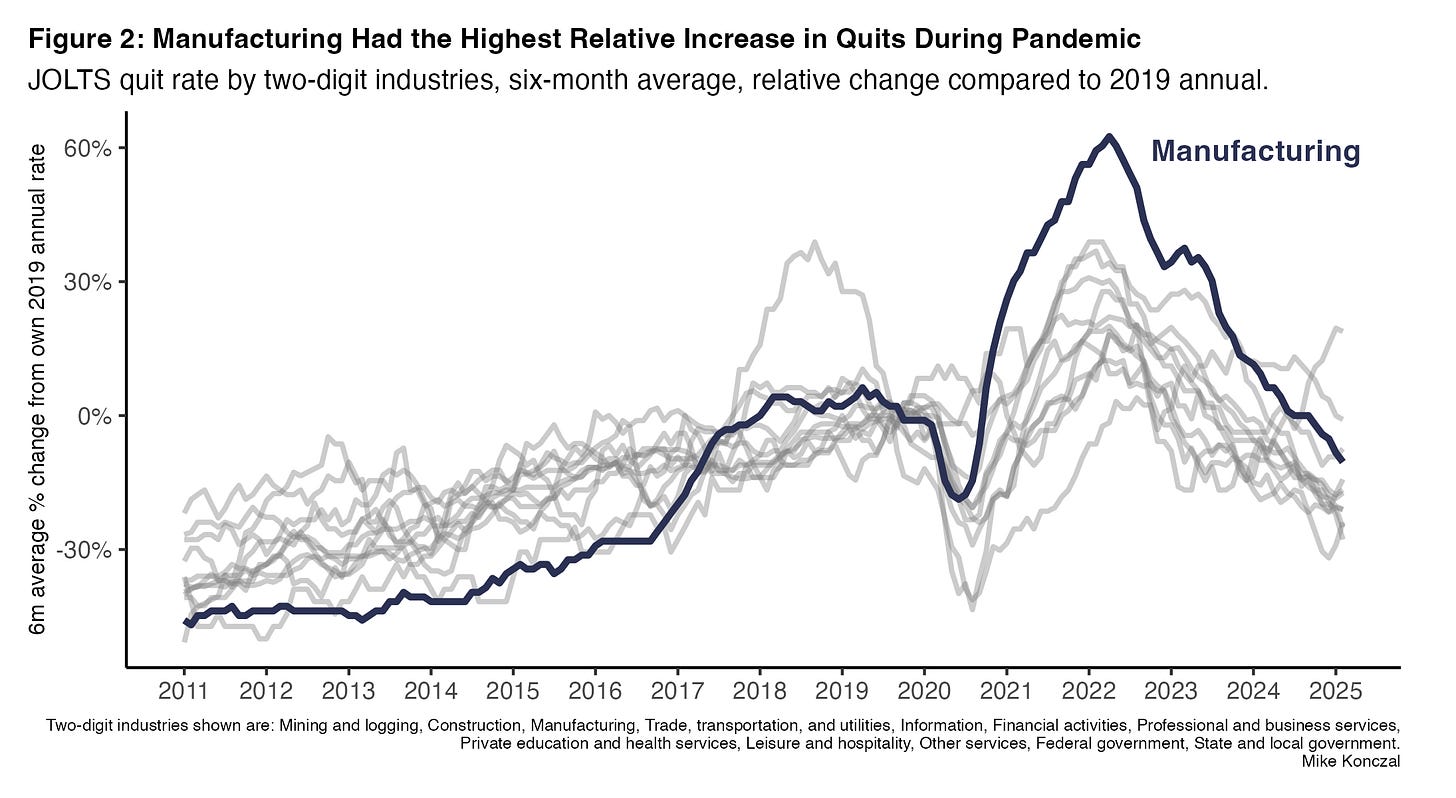

Instead of looking at what everyday people say, let’s look at what everyday people did when they had some income security and plentiful jobs opportunities. How did people with manufacturing jobs react to the labor market of 2021-2023, a period with a significant amount of job switching and where there was a peak of 2 job openings per unemployed worker? The answer surprised me. Manufacturing had the highest relative increase in job quitting and second highest, behind leisure and hospitality (of all industries), for absolute level. People with manufacturing jobs really wanted to quit them when they got the chance.

JOLTS Pandemic Overview (Feel Free to Skip)

The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) is a monthly BLS data source, like the jobs numbers or the inflation report, drawn “from a sample of approximately 21,000 U.S. business establishments.” Among other things, it tracks the rates at which businesses hire people, post active job openings, and experience employees separations.

Separations track layoffs and discharges, but the value economists follow closest is the rate workers quit their jobs. Quits are defined as “Employees who left voluntarily. Exception: retirements or transfers to other locations are reported with Other Separations.” Because it’s an interview of the business, not the person, it doesn’t know where people are going after they quit, whether that’s unemployment or a new job.

These values skyrocketed during the reopening. Figure 1 below is the six-month average of the total quits, job openings, and hiring rates from 2000 through now.4

People paid special attention to the quits rate in recent years. There was a lot of popular press coverage of the “Great Resignation,” or the large increase in quits and churn in the labor market starting in 2021. This often missed that the hiring rate was also historic, so a lot of what was happening could be described as a Great Upgrade to people finding better jobs. By 2023, there was Wall Street Journal coverage like “Job satisfaction hit a 36-year high in 2022, reflecting two effects of the tight pandemic labor market: The quality of jobs improved as wages and work flexibility increased, and workers moved into positions that were a better fit.”

There were other technical reasons. Economists worried the unemployment rate wasn’t conveying the strength of the labor market for purposes of how “hot” the economy was. They turned to the vacancy and quits rate, with (Bloesch 2024) making a good case quits was the better of those two. But the reason I focus is that quits are an affirmative choice by a worker, with the presumption that they are switching into a better job, or a better situation for them. The three above are interconnected; a quit creates a job opening that can then be hired. But of the three, it’s the one that’s a choice by workers to better their situation.

People Quit Manufacturing

So how did manufacturing do when it comes to the quits rate? Let’s define terms. The annual average for monthly manufacturing quits was 1.6% in 2019 and 2.3% in 2022. So it had a relative increase of 44% (2.3/1.6-1) and an absolute increase of 0.7% (2.3% - 1.6%). The monthly values only go to one digit, so let’s take a six-month average to smooth it out. Let’s start by looking at relative increases in Figure 2.

As we can see, manufacturing had the highest increase during the reopening. By a lot. But also note how much it increased by 2019, when unemployment fell to what were then recent lows and the Great Recession was far behind. How about absolute increase?

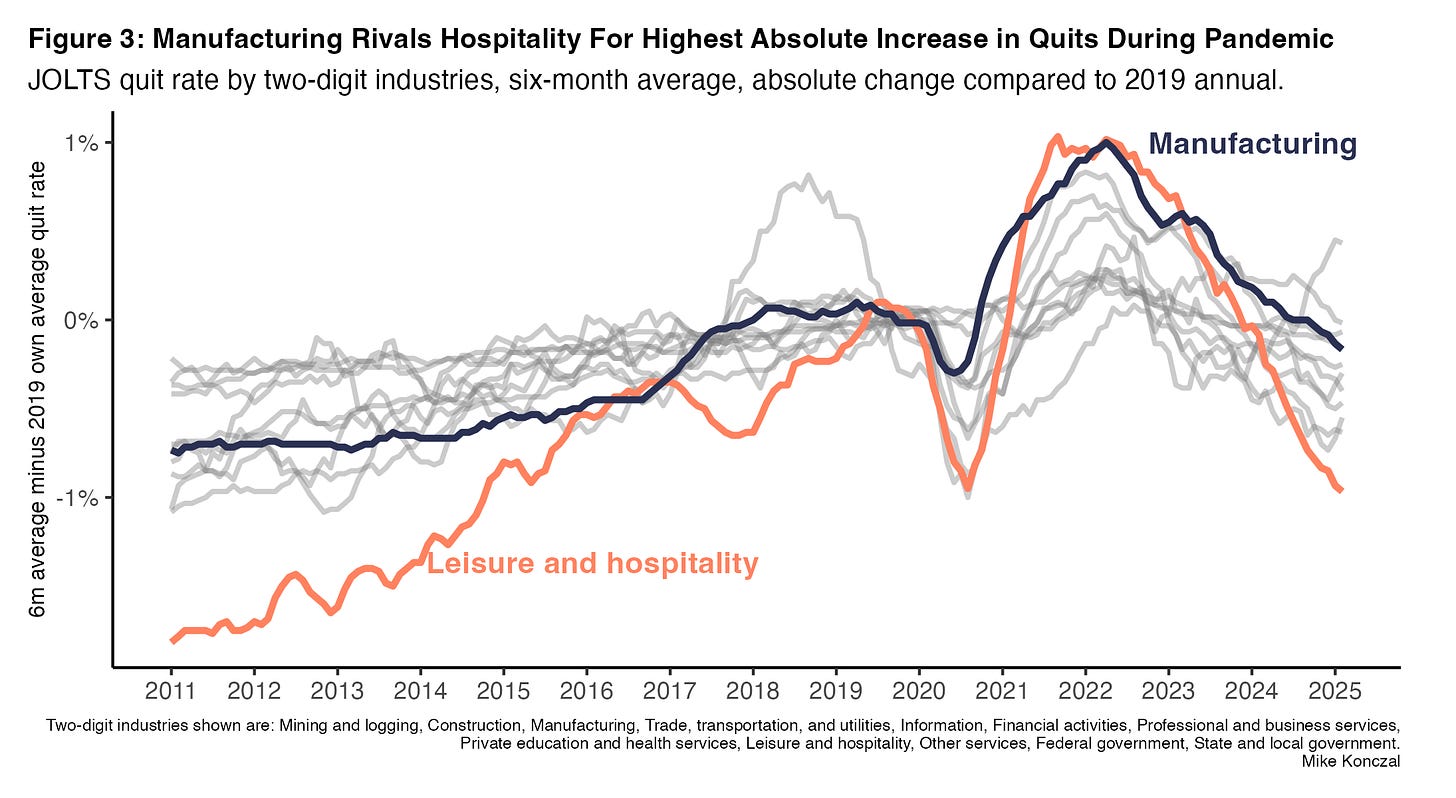

Figure 3 shows the absolute increase. Here it is mirrored by “Leisure and Hospitality” workers. This is even more damning, given the low wages and poor conditions in leisure and hospitality work. Workers took the historical opportunity of having extra cash and plenty of job openings to quit manufacturing jobs the same way they would quit working in industries like fast food or working in a hotel.

Now quits are increasing and so are hires. Manufacturing employment levels in 2022 and 2023 were higher than in 2019 as lots of economic activity moved from services to goods and investments picked up. Were the vacancies filled at a more rapid clip? Let’s look across industries by comparing the relative average increase in 2022 to 2019 (so a positive value is an increase) in Figure 4.

Here we can see people quit manufacturing jobs, which creates openings, and people are getting hired into manufacturing jobs. People with worse opportunities and situations take advantage of this to move into manufacturing jobs. And that’s fantastic. At the same time, for people already employed in manufacturing, they leave faster than anywhere else. Note that job openings skyrocket too - these jobs weren’t so uniquely desirable that they were easier to fill than other positions.

I use 2022 here because COVID itself was a major risk factor for in-person work during 2020-2021. But by 2022, with vaccines available, those elements are further in the past. The risks also run just as much the opposite way, that terrible working conditions made COVID worse just as much as COVID made terrible working conditions. I think many of the people romanticizing manufacturing jobs have forgotten when, in 2020, Tyson Food managers at a pork processing plant (probably NAICS industry code 311612, “Pork, primal and sub-primal cuts, made from purchased carcasses,” falling under Sector 31-33: Manufacturing) placed bets on how many of their employees would catch COVID.5

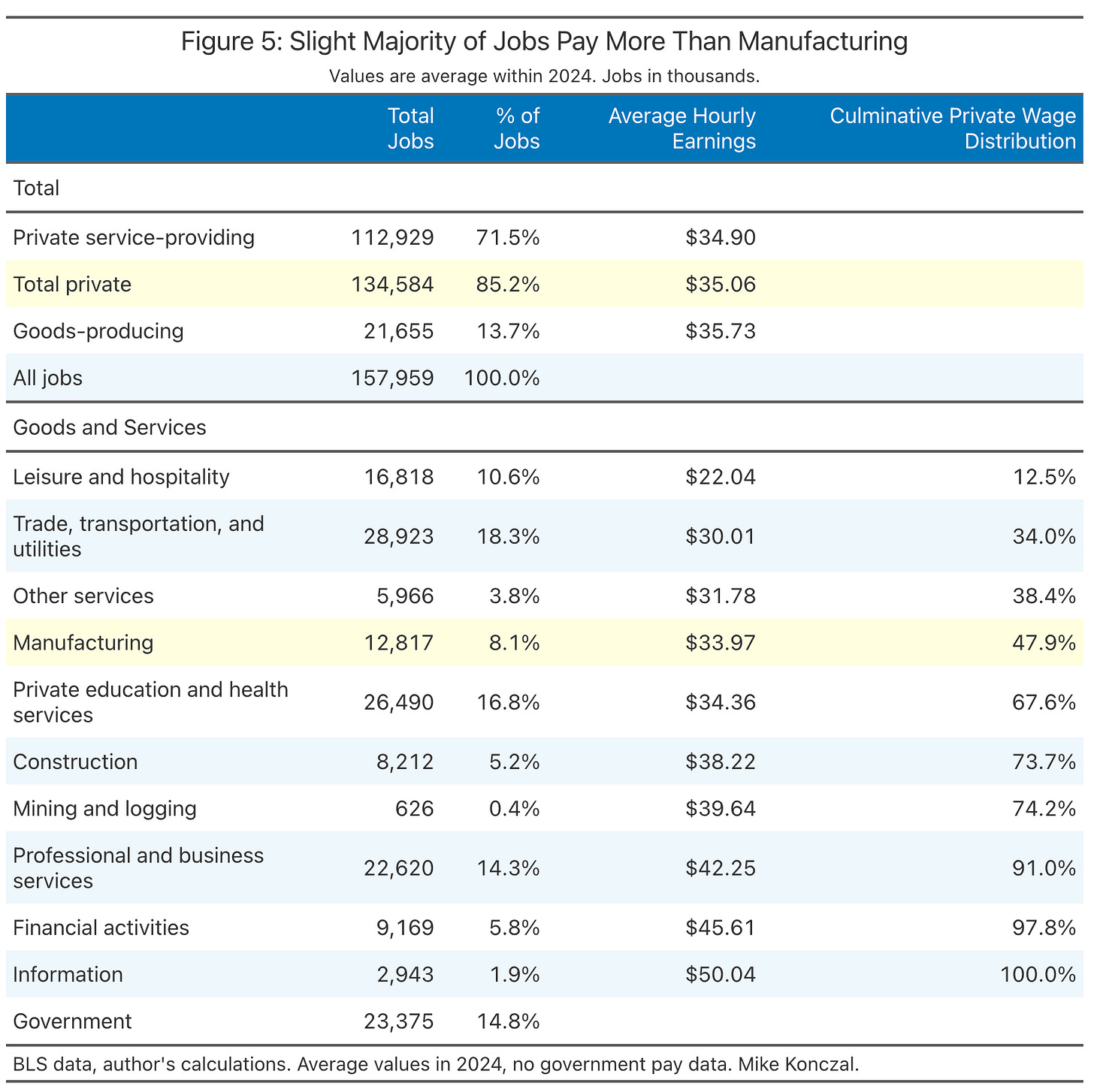

Cohn was right. Compared to email jobs, manufacturing jobs are hard. They also pay less. I don’t think people realize that manufacturing jobs pay just a little less than the average private sector job. Here’s a breakdown of how many jobs there are and how much they pay in Figure 5.

Rather than something to anchor a high-wage economy, manufacturing wages sit at slightly less than all private-sector jobs, both overall and just for services. There are things one could do to boost their wages (though we could also boost them in other jobs too). It does not surprise me that many people used the recent hot labor market to be hired into manufacturing from lower-paying industries, and that people already there wanted to leave.

Note from Figures 2 and 3 above that when there’s a recession or more general economic weakness, people are less likely to quit manufacturing jobs, just as they are less likely to quit any jobs. So the collapsing economic situation might help conservative intellectuals selling this vision. But whether it’s manufacturing jobs or a second Trump term, many people will seek other options after actually experiencing it.

Bob Woodward’s book Fear: Trump in the White House (2018), gives this JOLTS story citation to “multiple deep background interviews with firsthand sources.”

Tucker Carlson had a January 2019 monologue that I read as a precursor to this moment. “Any economic system that weakens and destroys families is not worth having. A system like that is the enemy of a healthy society.” On manufacturing:

Yet, the pathologies of modern rural America are familiar to anyone who visited downtown Baltimore in the 1980s: Stunning out of wedlock birthrates. High male unemployment. A terrifying drug epidemic. Two different worlds. Similar outcomes. How did this happen? You’d think our ruling class would be interested in knowing the answer. But mostly they’re not. They don’t have to be interested. It’s easier to import foreign labor to take the place of native-born Americans who are slipping behind.

But Republicans now represent rural voters. They ought to be interested. Here’s a big part of the answer: male wages declined. Manufacturing, a male-dominated industry, all but disappeared over the course of a generation. All that remained in many places were the schools and the hospitals, both traditional employers of women. In many places, women suddenly made more than men.

Now, before you applaud this as a victory for feminism, consider the effects. Study after study has shown that when men make less than women, women generally don’t want to marry them. Maybe they should want to marry them, but they don’t. Over big populations, this causes a drop in marriage, a spike in out-of-wedlock births, and all the familiar disasters that inevitably follow -- more drug and alcohol abuse, higher incarceration rates, fewer families formed in the next generation.

Jane Coaston covered it for Vox here. Far beyond questions over the “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar, I think this kind of argument is animating the intellectual actors of the Trump conservative movement, and why it’s willing to tolerate obvious damage and costs associated with the trade and economic policy moves.

Even on its own terms, the idea that ‘once men get jobs in the new USA textile and iPhone-assembly factories they'll have higher socioeconomic status, so women will want to marry them, and their new wages means women can stay at home, and this will reverse falling fertility trends’ is going to fail, and fail in catastrophic ways. Conservatives deserve better.

It’s worth noting that the manufacturing quits story holds whether you look at durable or nondurable goods. But given that a lot of the conversation is about e.g. shoe and textile manufacturing returning, I’m not going to concede that we should focus on just one of them at this moment.

I'm glad to see you point this out. Manufacturing used to employ lots of workers and thanks to union action pay them relatively well. Modern manufacturing uses a lot less labor per unit of output. Even textile work which resists automation is more labor efficient. Modern union busting and outsourcing have eliminated the good pay as noted in this article. Manufacturing is no longer a magic bullet for building a middle class. If anything is, it might more powerful unions, but those could help across the board.

There are good arguments for moving some manufacturing back onshore. National security is one. We import a lot of our high explosives from Poland, and with us dropping out of NATO a la Trump, we could lose access to this source. Another is to support important productive sectors like agriculture, transportation and medicine. Having the manufacturing closer both physically and culturally can speed innovation.

All told, thanks for the good article.