The Four Data Sleights‑of‑Hand Behind Trump’s Assault on Powell

What looks like a monetary policy debate is really a cover to take control of the central bank.

It's a dangerous time for the Federal Reserve. Last week, President Trump’s administration began building a case to fire Fed Chair Jay Powell, as Trump surrogates and right-wing media escalated direct attacks. OMB is probing the Fed, the GOP House Judiciary Chair has signaled willingness to investigate Powell, former Trump NEC director and Fox Business host Larry Kudlow is using his show to attack Powell, the Vice-President is posting, and Trump economic validator Oren Cass has declared “something is rotten” at the Fed. Reporters are scrambling to see if Powell will be fired.

The details of monetary policy are complicated. But at this moment of potential political takeover, it’s important to see that the conservative case against Powell’s monetary policy is built on four sleight-of-hand moves, four tricks where the conservative arguments don’t survive scrutiny. If Trump follows through on removing Powell, we should know just how flimsy the case was.

1. Trump Doesn’t Want One or Two Cuts. He Wants a Dozen Cuts and a Different Fed.

As a reminder, the Fed rate is set at 4.25% to 4.5%, and it cuts and raises in 0.25% increments. If you look at the financial community, there’s an active debate about whether the Fed should cut once, maybe twice, with others saying the Fed should stay steady or even increase rates.

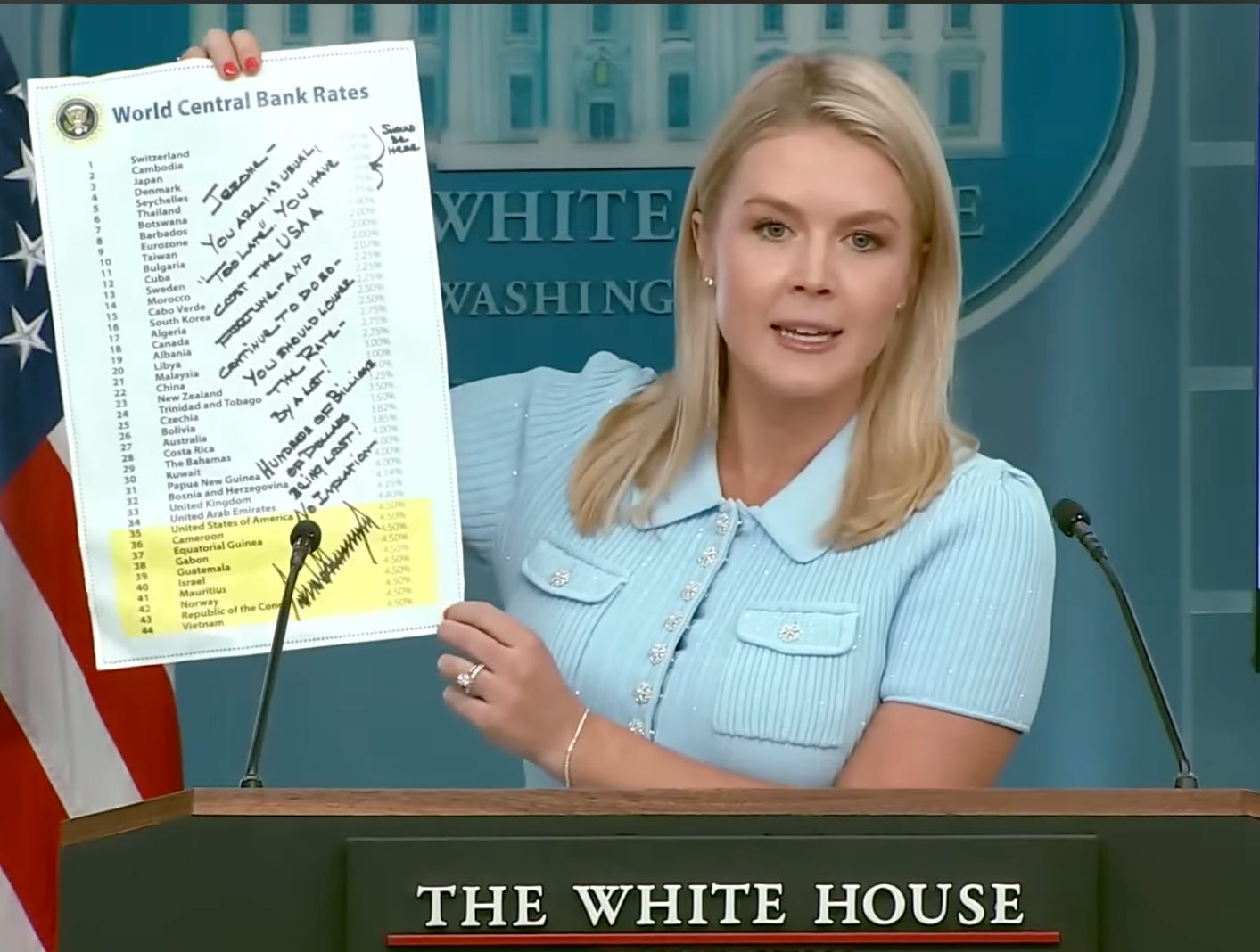

But President Trump isn’t calling for 1-2 rate cuts, he’s demanding 10-14. He has said that interest rates should be between 1% and 2%, and just this week called for a cut of 3 percentage points (equivalent to 12 cuts). He even sent a note to Powell stating this, shown in the press room and reprinted above.

There’s no economic case for a dozen rate cuts. But there’s a political one. Trump wants the Fed to cover for the debt explosion under his tax cuts. This is often called “fiscal dominance,” and it generally goes with weak central banks and political dysfunction.1

Even if you lower the stakes, asking the Fed to manage both the business cycle and the fiscal balance violates the Tinbergen Rule: for every n policy objectives, you need n independent tools. The Fed controls interest rates to manage the business cycle; adding a second objective, managing the debt load, requires a second independent tool, or else the Fed will fail at both.

It’s likely to fail. Large politically pressured cuts could raise the longer-term rates consumers and businesses face, if only from a political-instability premium. Or rates could become extremely accommodative into this stagflationary environment, risking more inflation. This, in turn, will have President Trump demanding more control.

An ordinary argument about whether the Fed should change rates at the margins is being used to mask the White House pressuring the Federal Reserve to take on a fundamentally different role. The White House is blowing out the fiscal deficit, and it wants the Fed to cover for it, no matter the cost to independence or long-term economic stability. This goes beyond the usual case for central bank independence, where the concern is politicians juicing short-term stimulus at the expense of longer-term inflation. This goes to whether the central bank should exist at all.

2. They Make a Cut Seem Obvious, When It’s Very Much Up for Debate.

I find it strange that the conservative movement, which is meant to have a temperament that avoids tearing down the fence of central bank independence without knowing why it was built, is willing to risk generational economic damage because the Fed might be off 0.28%.

You wouldn’t know that from their rhetoric. It’s not just the dozen rate cuts the President has called for. The Vice-President has said the Fed is “totally asleep at the wheel” and “they’re TOO LATE.” Others have argued that the Fed should have obviously already cut rates many times, and the only reason they wouldn’t have is fear of tariffs.

But is that true? Is it obvious that multiple cuts are warranted right now?

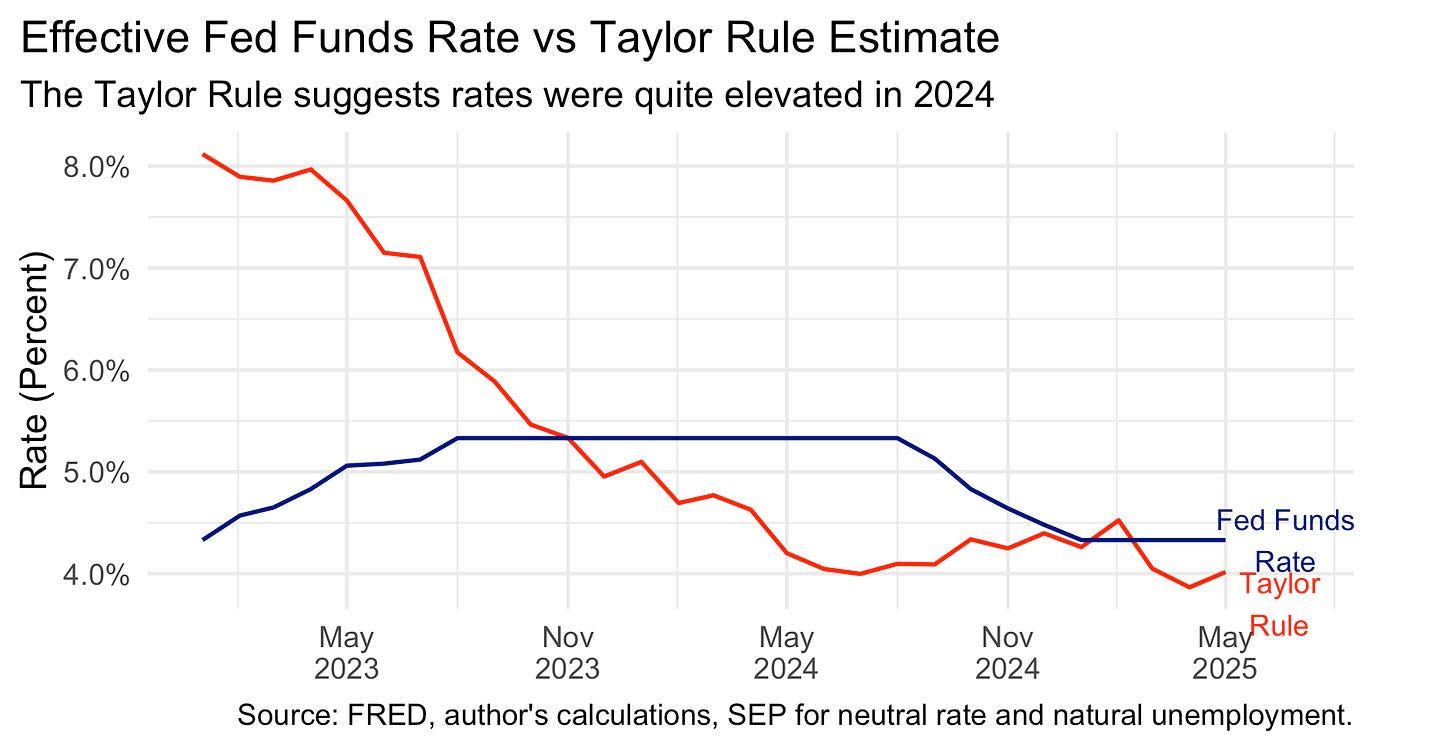

Let’s walk through the data. A straightforward way is to use a Taylor Rule, which is built on the intuition that the Federal Reserve should set rates based on a neutral rate of interest while balancing both deviations of inflation from the Fed’s target and deviations of actual output from its potential. Note the disagreement this method can produce, given you need to estimate two different unknowable values of potential output and neutral rates.

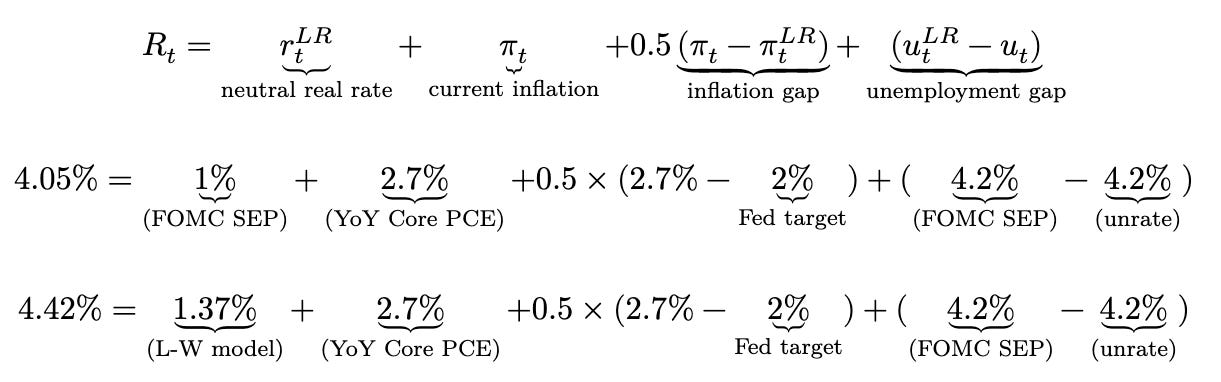

Let’s start with a standard Taylor Rule, adapted from the Fed’s own framework, along with two sets of assumptions, one normal and one conservative (temperamentally, not the actual movement):

The following bit is unfortunately technical, but it’s important. The current Fed funds effective rate is 4.33%. We take inflation from year-over-year core PCE. In the first version we take the neutral rate and natural rate of unemployment from the Fed’s FOMC SEP long-term values. This gives us a Taylor Rule of 4.05%, off by 0.28% or one cut. In the second, we take the neutral rate from the higher L-W model, as many people wonder if the Fed is too optimistic on its neutral rate, and we get 4.42%, right around where we are.

I’m on the dovish end of this spectrum, but think it’s telling of what a power grab this is to take over the institution based on 0.28% difference when many reasonable assumptions get you current rates.

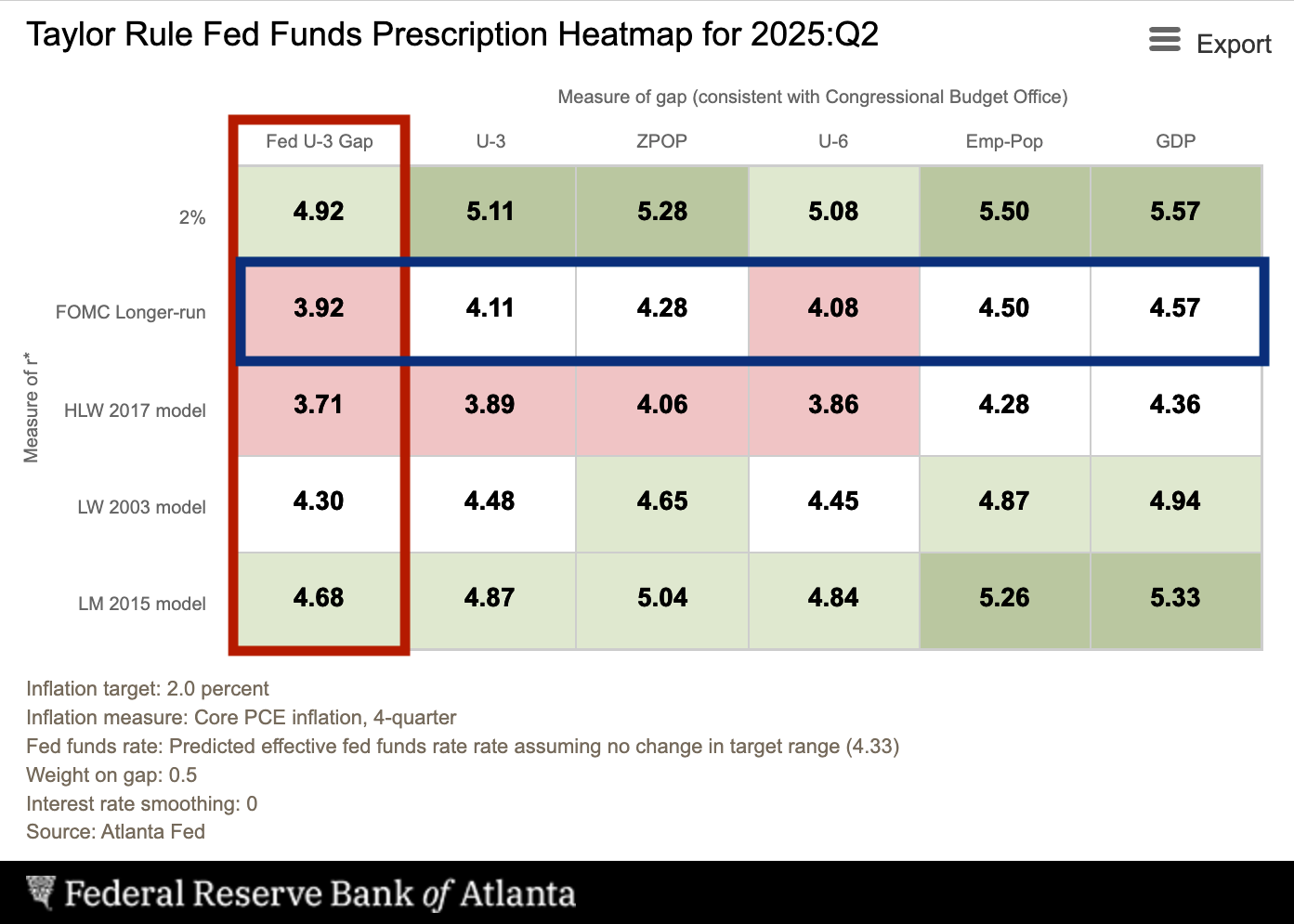

But to take this out of my estimates, we can look at regional Federal Reserve banks that have their own Taylor Rule approach, and they validate this finding. Here’s the heatmap produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Taylor Rule calculator, using a slightly different formula.

The horizontal spread is the different rates depending on the output gap, and the vertical spread differs on the neutral rate. As you can see from the superimposed blue box, using the FOMC’s longer-run neutral rate, there’s a range from 3.92% to 4.57% for rates depending on the output gap you choose. And assuming the Fed’s unemployment gap for output, the red square shows that different neutral assumptions can range from 3.71% to 4.92%. Reasonable assumptions can get you from 2 cuts to 1 increase. None get you to a dozen cuts.

You can also hit the Taylor Rule approach with a battery of modeling and forecasting assumptions, as the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland cleverly does at their site. They use 7 rules and 3 sets of data assumptions to get and display a range of values. For 2nd quarter of 2025 the 25th to 75th range is 4.1% to 4.5%, with the median value at 4.4%. This is in line with where we are.

The Taylor Rule isn’t the end-all of policy, but it gives us a baseline range and also provides us with ways for conservatives to justify the Fed being off. The output gap could become larger than we expect. But, after the immediate withdrawal of the maximum April tariffs, it’s unclear how much unemployment will increase. Even in the immediate aftermath of Liberation Day the worry was 4.7% unemployment, in which case forecasters anticipated rapid cuts, and that has backed down dramatically. The same administration pointing out unemployment hasn’t gone up is at the same time weakening the case for cuts.

It could also be that inflation is far lower than we realize. Certainly that’s their talking point, with an example of Larry Kudlow saying “I think inflation is 1.4% at an annual rate.” But this is wishful thinking. PCE remains elevated in the mid-2% range. You can rely on CPI, which is unusually lower than PCE for the time being, but the Fed doesn’t do that. Even in recent months, core PCE inflation was 2.7 percent annualized from January to May, 2025. Stylized metrics over short time-horizon don’t give us the full inflation picture that remains above target.

Rates are within a reasonable range given the fundamentals. People can argue at the margins, they always do about monetary policy, but there’s no evidence the Fed is far outside where they should be.

3. The Same Argument Providing Restraint Now Called For Cuts Last Year

There were cuts last year in 2024. Some conservatives are arguing that this reflects political bias, that Powell cut for President Biden but won’t for Trump. As Vice-President Vance tweeted, “I’d love to hear an argument for why Powell cut rates 50 points right before an election but can’t do it now with inflation lower.”

I can give one. Let’s use simplest version of the Taylor Rule above, the first one that gave 4.05% now, and run it backwards with the same assumptions:

Here we can see that rates were far more restrictive, for much longer, in 2024 (the blue Fed rate was higher than what was implied in the red Taylor Rule), than what we have right now. Moreover, we saw the “Sahm Rule”, which is an important recession warning based on the acceleration of the unemployment rate, trigger by going above 0.5, as unemployment went from 3.5% to 4.2% in a short period, leading to worries unemployment was increasing too fast.

These are two distinct but overlapping conditions. In 2024, rates were both obviously restrictive for a long time, and something in the economy, the Sahm Rule, was worrying in a way that reasonably predicted future weakness. In 2025, rates are not obviously restrictive now, and haven’t been for a while, and there’s no indication the economy is slowing at a pace to trigger action.

The 2024 comparisons are completely off unless someone can give me something more specific.

4. The Fed is Correctly Concerned With Second-Order Tariff Impacts

Critics claim the Fed is panicking over tariffs simply because they raise prices. That’s a caricature. The actual concern is about how tariffs are affecting expectations and feeding second-round inflation pressures.

Oren Cass attacks Powell for not understanding inflation based on Powell’s House Financial Services Committee testimony in June, where he responded to a question by saying “some significant inflation will show up from tariffs. And we can't just ignore that.” Cass says that a one-time increase in prices is not “cognizable for monetary policy.” But here’s what Powell says clearly in his opening:

The effects on inflation could be short lived—reflecting a one-time shift in the price level. It is also possible that the inflationary effects could instead be more persistent. Avoiding that outcome will depend on the size of the tariff effects, on how long it takes for them to pass through fully into prices, and, ultimately, on keeping longer-term inflation expectations well anchored.

The FOMC’s obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored and to prevent a one-time increase in the price level from becoming an ongoing inflation problem.

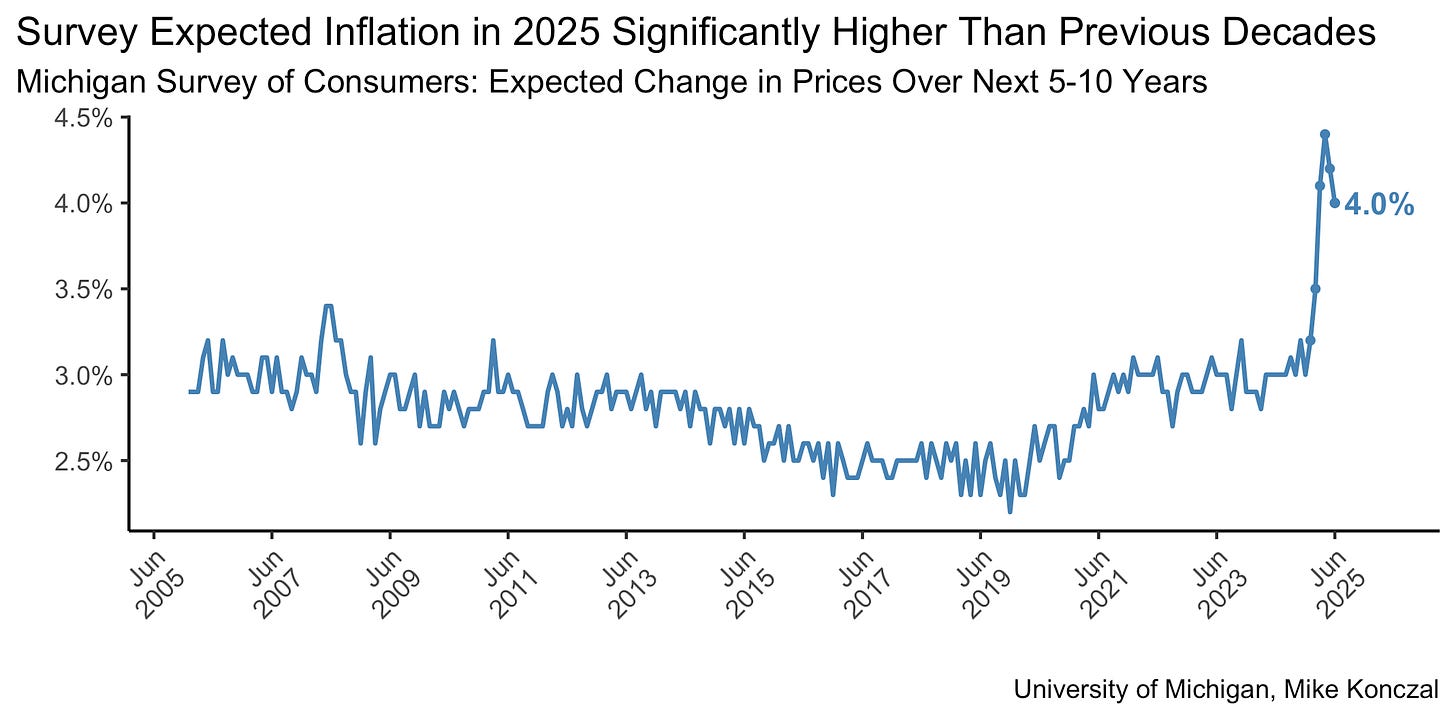

This isn’t just Powell, many FOMC participants believe this. And there’s reasons to take it seriously. The University of Michigan survey’s inflation expectations for 5–10 years ahead just spiked. That didn’t happen during the 2021–22 inflation wave. It’s happening now. That’s a red flag.

Of course this could just be noise; it’s not reflected in the hard financial data. Sentiment trackers are no longer as predictive of economic activity in the post-pandemic period (Hoke, Feler, Mitchell, Chylak, 2025). But if we were to wait for this to end up in the financial markets or professional forecaster community, then it’s probably too late and you’d need a recession to get it out of the system.

I’d go further than this. Cost-push shocks can be looked through, but a tariff brings extra liabilities as a cost-push shock. They lower GDP in a way that pressures the output gap, and their “inherently stagflationary” nature complicates straightforward monetary policy analysis compared to other shocks (Auclert, Rognlie, Straub, 2025). More, that so much of the current tariffs are on intermediate inputs risk more persistent inflation in a way they wouldn’t if they just faced final goods (Cuba-Borda, Queralto, Reyes-Heroles, Scaramucci, 2025).

My weak baseline is that these won’t pan out in a substantial way. But given the unique situation, and with the labor market stable, why should the Fed completely ignore the potential risks?

The conservative attempt to take over the Federal Reserve isn’t about Powell being off by one cut. It’s about whether the Federal Reserve can continue to exist as an independent institution. Trump and his allies aren’t arguing for better policy. They’re arguing for a Fed that does what they say, because they’re running up deficits and want someone else to take the hit. If Powell is removed under these pretenses, the consequences will outlast any single rate decision.

Note that there are extreme times you might want to do this, like the United States did during World War II. And it is interesting as an academic exercise. During the 2010s there was some interest, often associated with people in the MMT world, about “functional finance,” where the central bank manages the debt, and the business cycle and inflation are instead managed by either the fiscal authority (Congress) or administrative and regulatory agencies. (This argument is less prominent following the recent inflation episode.) But Trump and people in his orbit are proposing no such justification or any sense that there’s a secret plan to fight inflation after the takeover, besides the President tweeting at companies.

"Avoiding that outcome will depend on ... how long it takes for them to pass through fully into prices,..."

Forgive my dumb question: Does this mean that companies temporarily eating some of the tariff costs to slow sticker shock could cause problems with more persistent inflation.

Two words: Russell Vought. This evil piece of shit is behind everything destructive in the convicted felon’s agenda. Which is, well, everything. Shine a bright light on Vought. I mean a laser focus. And don’t let up.