When Reality Isn't Bad Enough: Trump’s Fake ‘Private-Sector Recession’ of 2024

In which we dive into the labor market of 2024 and the question of whether an increase in health care jobs is evidence of or justification for a recession.

Were we in a secret labor market recession in 2024? Was the labor market experiencing a ‘private-sector recession’ as the Trump administration took over? No. But as the reality of Trump's disastrous trade war and the growing threat of an actual recession set in, we’ll hear more of this excuse from Trump officials. It’s wrong—and worse, the Trump team's current actions represent the most harmful response possible to any underlying economic slowdown.

Summary:

The Trump administration is preemptively blaming a potential recession on the fact that job growth in 2023–2024 was largely driven by government and health-care sectors.

Creating ‘only’ 47,000 jobs per month in 2024 after excluding less cyclical sectors is neither evidence nor justification for a recession.

Employment shares in health care and government fell sharply during the pandemic and are now experiencing a normal catch-up, remaining below historical trends.

The proportion of industries experiencing negative job growth is within a typical, non-recessionary range, though the most cyclically sensitive sectors have indeed slowed, echoing trends seen in 2019.

The most likely causes of any slowdown are rising interest rates and political uncertainty, both significantly intensified in 2025 under President Trump.

The Trump Team’s Case

Most of the time government officials are talking up how the economy is doing, and avoiding any hints of an oncoming recession. Yet right now, the Trump administration is telling people to brace for necessary pain to recover from a recessionary labor market.

Recessions are scary businesses. Businesses fail, people lose their homes, and the impacts persist. Downturns take on a life of their own as weak spending and investment reinforce each other. If the Trump administration believes we need to have one we should closely interrogate why.

So what’s the case? Here’s Stephen Miran, chair of the Council of Economic Advisors for the Trump administration, the chief economist of the White House, on the Bloomberg Balance of Power Podcast (March 23rd, my bold):

Host: But even Trump and his advisers, including your colleagues, Elon Musk, Scott Bessent, the Treasury secretary, and others, are signaling a no pain, no gain concept here, that for a little while things could get bumpy in the economy.

Stephen Miran: Yeah. So there are some risks in the economy, but I think those risks predominantly derive from the transition from an economy which was primarily government driven to an economy that's primarily private sector driven. And that may contribute to make things bumpier and less robust in the short run. And just to give you one number that's a great example of that is if you look at the shares, the share of jobs created in 2023 and 2024.

So the second half of the Biden administration, when COVID is over and it's really just a result of Biden administration policies, 73% of all jobs created in those two years were due to government and government-adjacent sectors. But government adjacent I mean, sectors like education, sectors like health care, social assistance. These are sectors of the economy that derive a very large or maybe even in some of them, the majority of their financing, ultimately from the taxpayer through direct transfers or subsidies. So three quarters of jobs created in the last couple of years came from basically, you know, sort of government expenditures and taxpayer subsidies. So it is a brittle economy as we transition away from that to the private sector.

But the Fed and Fed officials are correct then that there will be at least short term pain as tariffs kick in. So I don't think that there's going to be material short term pain from the tariffs. I think the short term pain is coming from the reorientation of the economy, from the government to the private sector.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has repeatedly claimed the “private sector has been in recession,” echoing the argument that job ‘growth in the past 12 months has been concentrated in public and government-adjacent sectors such as health care and education.’ You can read more about that from Victoria Guida and Courtenay Brown. This is different from the economy just having slowed down, or some measures, like hiring, slowing a bit too much.

So were we in a secret recession? Nobody thought this in real-time. The Economist’s “envy of the world” feature was typical of economic coverage. Real GDP growth in 2024 was 2.5%. Over 2023-2024 it was 2.9% annualized. Each is higher than the 21st century average of 2.1%. Ernie Tedeschi recently had a good overview of this and the other positive economic indicators heading into 2025 at Equitable Growth.

But I’m going to stick with the labor market and their argument. Let’s look at the increase, level, and distribution of jobs.

Job Increases Are in Line With a Healthy Economy

So let’s chart out their data points. Figure 1 has the relevant figures for job growth across the four sectors in question, government, “private education and health services” which are broken down into the two categories, and the rest of the economy, for recent years (2020 excluded).

I think we can stop here and say that the fact that there were ‘only’ 47,000 jobs created each month in 2024 when you exclude major a-cyclical categories is not evidence of or justification for a recession. There is no negative job growth being covered by these categories. And what is even a baseline number here? Estimates of steady-state employment growth vary widely (here’s a calculator from the Atlanta Fed to run your own) but one estimate from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco places the long-run break-even rate at “70,000 to 90,000 jobs per month” including health, private education, and government.

We can use 2019 as a comparison baseline. There was the same amount of total nonfarm job growth per month, around 165,000. 2024 had ~32,000 more in health care and ~20,000 more in government, primarily local government. Nothing about this says there’s a secret or necessary recession in the background here.

It’s also worth reminding people recessions don’t rebalance economic activity. Jobs in all industries go down. That’s just the empirical reality of a recession. If you want to move people from one specific sector to another you need micro tools, and a recession will not accomplish that.

The Level of Jobs Are on Trend - With a Notable Exception

Is the level of government and health care employment out of whack? No. Health care and government employment lagged during the recovery and it makes sense that they are increasing more at the end of a business cycle. Let’s next look at the share of employment and its change since 2019 in Figure 3, and in Figure 4 look at employment share over time for select industries, with a trendline from 1991 to 2019. That’s not a forecast or a prediction but it gives some sense on how things have evolved.

Here are some things I see in this:

Health care had a big downturn during covid and its catch-up growth is on trend. Without further evidence, the idea that health care jobs are taking up too much of the economy isn’t true. It’s been growing and will continue to grow and, if anything, could pick up more.

Government is down below a declining trend, driven by declines in local government share. Catch-up there makes sense as well.

Manufacturing is down as a percent of the labor market, but it’s actually above where you’d draw the trendline. If the goal is to increase manufacturing employment, slowing the decline is probably the best outcome, and the investments made over the past four years did that.

The biggest thing that happened in the labor market was taking almost half a percentage point of employment in leisure and hospitality and moving it to much higher paid business and health care jobs. That is around 600,000 people upgraded in their employment.

This last point hasn’t been covered enough. We fret about how to create good jobs and assume that’s going to be in manufacturing, even though, as seen in Figure 2 above, manufacturing jobs have lower pay than either the average job or those in health care. But the biggest legacy of the past few years was being able to move people from low-wage service jobs into medium-wage ones.

A mom working fast-food jobs to make ends meet was able to take stimulus checks and income security and a fully refundable CTC and get the education and resources to find a much higher-paying job as a nurse or an EMT. In turn, that Great Upgrading allowed other service sector workers to demand higher wages and compress inequality in the bottom half of the income distribution.

But none of this evidence suggests that the economy is secretly in recession.

Distribution of Jobs

Ok, the level doesn’t justify this. But how is the distribution of jobs within the labor market? Is it hiding a secret recession? No. Here’s the diffusion index, which takes 250 sub-industries that make up the labor market and tracks what percent are gaining jobs each month.1 If it goes below 50, where more narrow industries are losing jobs than gaining jobs, there’s generally a recession happening.2 It’s been pretty steady, a bit slower than 2019 but still positive.

One important lesson from this is that in both expansionary and normal times 30-40 percent of sub-industries will lose jobs. If the idea is that we’re in a secret recession because a substantial amount of negative job growth is covered over by other sectors, then we are always and have always been in a secret recession.

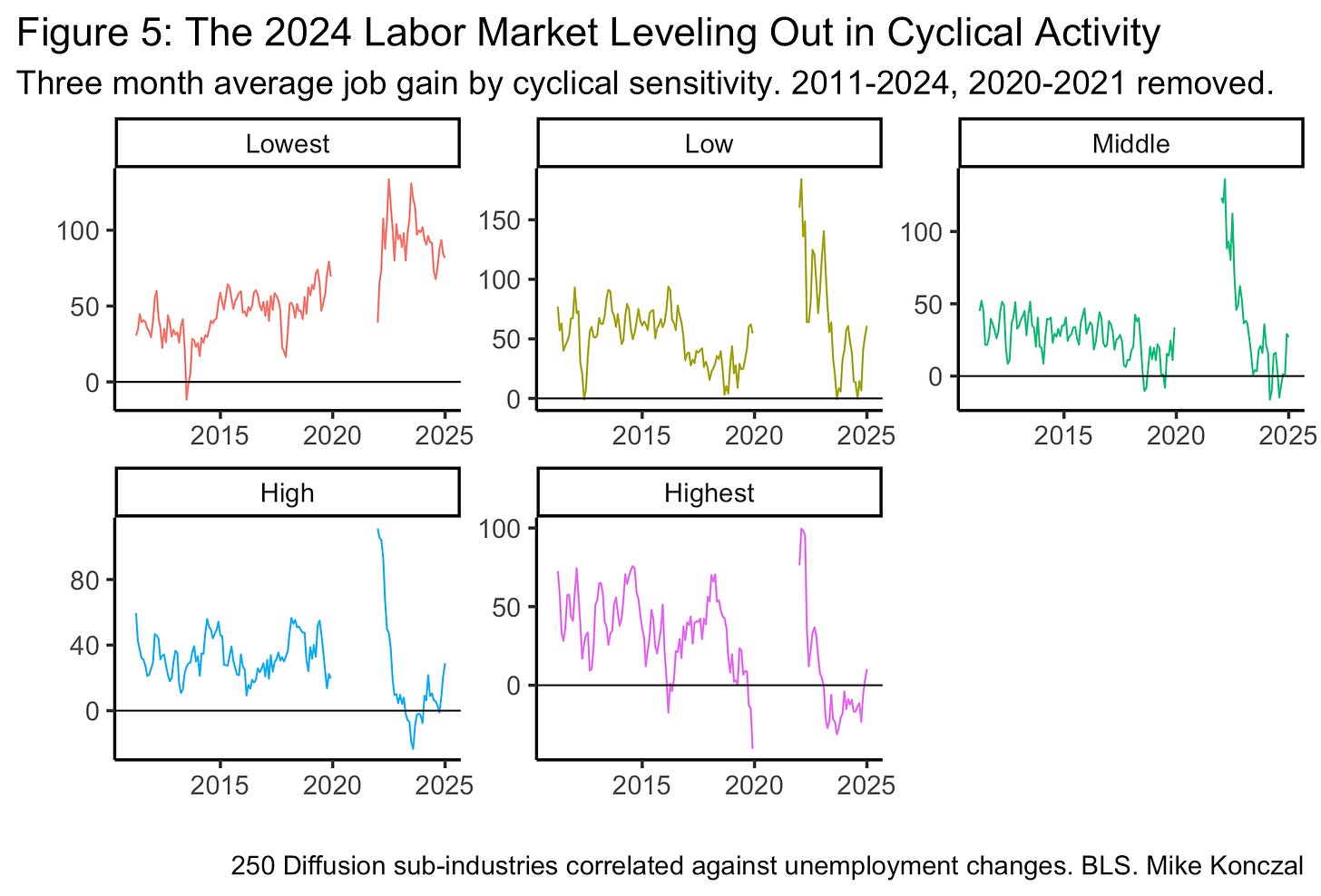

However, as the economy has slowed, there has been a slowdown in the most cyclically sensitive industries. I take the 250 categories and break them into 5 categories of cyclicality, with the methods in a footnote.3 Let’s see how each category has grown year-over-year in Figure 5, which excludes 2020 and 2021.

And here we can see some weaknesses. The most cyclically-sensitive jobs started to lose some employment. It did the same in 2019. Moreover, the hiring rate slowed in 2024, raising the possibility that unemployment may increase due to fewer people finding work rather than more people losing jobs.

I generally saw three reasons for this in 2024: like in 2019 it’s the end of a major business cycle, interest rates have been and remain in restrictive territory, and political uncertainty, especially about who would be the next President and what they would do.

So restoring some cyclical activity would be good here, and the best way to do that is for interest rates in the economy to decrease and certainty to level out. So what is this administration doing? It’s pushing a tax bill that leaves many families worse off and inflates the deficit in a way unlikely to spur investment or spending. Simultaneously, it has launched an ill-conceived trade war, creating uncertainty, driving up inflation, reducing real incomes, and fostering stagflation. All of these outcomes raise interest rates and limit the Fed’s options.

I don’t find this “secret 2024 recession” argument convincing, and I doubt voters will either. When an actual recession comes, they’ll only have themselves to blame.

Searching “diffusion index” at the BLS Methods webpage will give you a CES diffusion index series spreadsheet with all the categories. Per the methods, the 250 sub-industries are from “using all employee estimates at the 4-digit NAICS level. If the lowest level published is at the 3-digit level, then that 3-digit NAICS is used.”

The one-month value of the diffusion index (which isn’t on FRED somehow, which needs to be fixed) fell below 50% in July 2024, the same month the Sahm Rule was triggered. Though every other metric was fine, it was a scary moment. The Fed cut more aggressively likely because of those two events and the then knowledge that future QCEW revisions would reduce CES payroll numbers; in doing so, of course, it reduced the predictive linkage between the metrics and recessions!

The Biden CEA was actually ahead of the curve on this question of whether the labor market was lopsided, here they are in June 2024 diving into diffusion metrics. I take a version of their methodology here, regressing six-month employment percent change on six-month unemployment rate change for each individual sub-industry, and then break them into 5 quantiles.

The code for all the graphics is available here. If you are career planning and want to see the regression coefficients on unemployment for each sub-industry check here. The value closest to zero (0.0061) is “Other transit and ground passenger transportation.”

Not to mention how essentially fucked up it is to categorize jobs in health care, education, and other government services as economic negatives. Sacrificing the caring economy for private wealth; so the rich can get richer.

I appreciate this piece, although I'm not sure that you've rejected the premise, so much as believe "it's not so bad." To be fair, it's not just Trump that's been concerned with Labor Market Breadth -- Skanda Amarnath (of the leftwing Employ America) is too https://www.therandomwalk.co/i/157970235/people-are-worried-about-labor-market-breadth