The Three Open Questions When it Comes to Our Cost-Push Supply Shock Inflation

In which we seek to lock down better answers for everything that just happened in light of the historic disinflation of the past year.

The annualized six-month change in core PCE inflation was 1.9 percent in November 2023, below the Federal Reserve’s target of 2 percent. That same six-month core number peaked at 5.9 percent in March 2022, remained at 4.9 percent in November 2022, and averaged 4.8 percent in the first quarter of 2023. Inflation falling by 3 percent within a year while unemployment is below 4 percent the entire time is simply unheard of outside the supply shocks in the aftermath of World War II, as we can see from this similar CPI graphic above.

Though it may rise or be seasonally readjusted in the months ahead, and housing and health care will keep a persistent wedge between PCE and CPI inflation, this is a major change in the inflation story. This goes far beyond a ‘soft landing,’ which was generally the idea that we could get PCE under 3 percent while unemployment remained below 4.5 percent. And it’s more than we’ve just entered a new phase of this recovery where it’s necessary to discuss the path of rate cuts. This disinflation is the kind of development that should cause us to reassess everything that happened over the past several years.

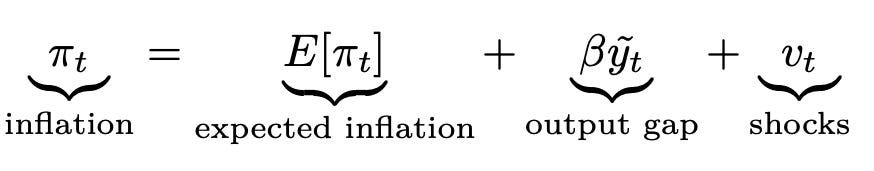

So far the idea that has gained prominence is that this whole experience was the process of a major cost-push supply-side shock, the kind of argument associated with ‘transitory’ inflation in 2021. (In the Phillips Curve, our attention is away from the demand-driven output gap and back towards shocks.) Here’s Greg Ip with a good overview thread1, and The Economist with a skeptical reassessment.2 Certainly, this cost-push argument is much stronger than it was over the past two years when it fell out of favor.

However, there are (at least) three parts of this cost-push thesis that I think need some additional thought. Parts where the counter-arguments are still ongoing, or ones where there are several different answers, or elements where we’d all benefit from sharpening our theory and evidence. The three counter-arguments for the cost-push thesis are:

The reversal of a supply shock should reduce the price level (i.e. deflation), not the rate of growth of the price level (i.e. disinflation).

The inflation was too broad to be associated with a supply shock.

The heat and subsequent slowdown in the labor market, especially job openings, indicate a strong role for demand.

The questions are related and the answers overlap, but it’s worth taking them one at a time. I’m not going to give a definitive answer here; I don’t have one. But I’ve been thinking more critically about these questions over the past weeks. Also since watching Iván Werning’s AEA talk on his work on inflation since the pandemic (video, slides) and revisiting those papers, I think there are good arguments available worth pulling out. Let’s dig in.

1. The reversal of a supply shock reversal should be associated with deflation, not disinflation.

We have three relevant kinds of supply shocks to think about here: the inputs into production that have reversed (e.g. shipping) and those that continued at a higher price level (e.g. some PPI inputs), as well as the relative price of final items in the consumption basket (e.g. core goods). But as some inputs come down, what should happen?

I’ve seen this argument on X (e.g. David Andolfatto, David Beckworth, John Cochrane) and Fed governor Chris Waller recently said it: if a supply shock raises the price level, when the supply shock goes away the price level should fall. Or as Waller says, “The level of inflation is permanently higher. That doesn't happen with supply shocks.”

Can it happen? Here the discussion has been between static AD-AS models and forward-looking DSGE models; let’s do something in the middle. Here’s a three-equation New Keynesian model with backwards-looking inflation expectations from Wendy Carlin and David Soskice (2005). They make a good case that this approach, which emphasizes a forward-looking central bank balancing priorities, should take over for undergraduate static intermediate macroeconomic approaches. (Kudos to DIY Macroeconomic Model Simulation site for R coding up a base model this adapts from.) It certainly allows you to follow how things are moving.

These are rates; supply shocks enter through the Phillips Curve. Let’s do three exercises: (1) a supply shock that fully reverses (the rate increases and then the rate is equally negative) with the Federal Reserve acting to offset it, (2) a one-time supply shock , with the Federal Reserve acting to offset it, and (3) a supply shock that fully reverses, with the Federal Reserve looking through it and keeping output steady. How does it look?

The first row is the supply shock, the second is the real interest rate the Fed sets, the third is output, and the fourth inflation. In the first scenario output falls and then increases, and there is subsequent deflation. In the second, output falls and there’s a one-time increase in the price level. In the third, output is steady, and there’s a one-time increase in the price level. The third scenario shows us, counter to Waller, that a supply shock can increase the price level even if the shock fully reverses.

More, this shows us that the price level doesn’t fall after a supply shock unless something forces it. As Iván Werning notes, “If gas prices led other goods to rise, we are now at a new price level even after relative prices for gas are back.” And the thing that would force it to fall is higher interest rates leading to a recession (i.e. periods of declining output). For the scenarios, I think we had a mix of all of them, with the third being the most relevant. Some observations:

GDP growth was negative or near zero in the beginning of 2022 for two quarters. (Remember the debate about whether that necessarily demarcates a recession?) Productivity also took a hit during that period. Maybe time to revisit this?

We had strong growth in 2023.

Interest rates haven’t been at the levels associated with a Taylor Rule, the level associated with trying to offset the full supply shock.

As Lorenzoni and Werning’s BPEA paper Wage-Price Spirals develops, in the case of a supply shock, it may be the optimal policy to keep GDP steady: “If we start at a zero-output-gap policy, with positive price inflation and negative wage inflation, the effect can be welfare improving because the welfare cost of price inflation is smaller than the welfare cost of wage deflation.”

There’s a lot of levels and rates, inputs prices and final prices here, so it’s easy to get tripped up. But from the current moment, getting through the inflation, instead of causing a recession because we didn’t have enough semiconductors (a recession that may not have even slowed inflation much), looks like the optimal choice.

2. The inflation was too broad to be associated with a supply shock.

That inflation broadened out of categories directly hit by the supply shocks of 2021, far more than the idea that inflation took too long to come down, is what killed the transitory argument and put it out of commission until recent months. Academics who had focused on the supply side elements in 2021 (Ball et al. 2021), started worrying about measures designed to exclude outliers, like median CPI, which were increasing (Ball et al. 2022). I too was worried about this at the time.

But what should I have expected? Let’s approach it a different way. I had a riff I’d do in presentations about inflation about whether relative prices can increase inflation. I’d ask people if they stopped going to a salon or a barber shop as much, and hands go up. Hands would also go up when I asked if they bought more home grooming products instead. I then would ask if the price for a salon or barber shop trip had fallen, and people would say they hadn’t, though the price of the equivalent goods had gone up. Then I’d show this graphic to show their experience was economy-wide.

This is economy-wide quantity and prices from the national accounts, with the price on the y-axis and quantity on the x-axis (like an AD-AS picture). We can see for “hairdressing salons and personal grooming establishments” that the quantity consumed drops 74 percent in a matters of months during the beginning of the pandemic and, more notably, at the end of the summer of 2021, well into the reopening, the real quantity is still down 35 percent. But the price of going to a salon hadn’t fallen at all. Meanwhile people started spending a lot more nominal dollars on “personal care products,” first buying a lot more of them and then paying a lot more for them, like a backwards L.

Sectors of the economy have downward price rigidities and convex supply curves - that’s a pretty big insight! I’d joke that as a bald guy I bought my head shavers before the pandemic and wasn’t contributing to inflation; then I’d then do the big reveal, and show that this same story is true for goods and services as a whole:

So it was good to see this graphic in Werning’s presentation, which gives the fancy New Keynesian model for this empirical observation:

The model and research comes from Monetary Policy in Times of Structural Reallocation (Guerrieri, Lorenzoni, Straub, and Werning). They find that this “asymmetry naturally manifests itself as an endogenous cost-push shock” and “resulting in inflation optimally exceeding its target.”

But what happens when demand comes back to Sector A (salons, services) in this view? At the time, we all just assumed it would pick up with normal pre-pandemic rates, though that didn’t happen.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made inflation worse in 2022. However we should consider that the relative prices, the answer found in New Keynesian models, played a role here. Workers, in particular, had better, upskilled options in the expanded sectors, so wages were needed to pull them back. (Leisure and hospitality employment levels are still just below their pre-COVID peak.) Real wages and the labor share fell during this reopening, but there was serious wage compression that reflected these sectoral shifts.

More from Lorenzoni and Werning’s BPEA paper Wage-Price Spirals: “The fact that the response of pt lags the response of pXt shows that our model features a clear mechanism for pass-through from non-core [supply] inflation to core [overall] inflation […] the fact that pXt [supply] is falling after jumping at t = 0 is not in contradiction with the fact that supply constraints are crucial for the inflation episode. It is the level of pXt, not its rate of change, that reflects the underlying scarcity in the economy, i.e., the a high labor to non-labor inputs ratio nt − xt , and this scarcity is a crucial driver of the high inflation rate.”

3. The heat and subsequent slowdown in the labor market must indicate a strong role for demand.

I think less is at stake here, and there’s a couple different arguments here. I want to stick to the one I’ve seen the most, which is that the increase and decrease in job openings reflect increasing and decreasing demand along a nonlinear Phillips Curve. Gauti Eggertsson’s research makes a version of this argument. I think the counterargument is that labor market dynamics aren’t characterized by too much demand (as in a Phillips Curve) but instead about resorting and upskilling in the labor market. Those kinds of dynamics (e.g. job-to-job transitions) aren’t well captured by Beveridge Curve style analysis.

First: job openings haven’t fallen fast enough to be in line with the disinflation we’ve seen.

Second: Job openings and quits increase and decrease with employment-to-population ratio increasing, like an upside-down U. We can see this at the state level as well.

Third: quits have fit the data much better than openings during this time period, and if you put quits more central in the story you can see how it’s about dynamism rather than simply demand.

There’s more to discuss, but this is a good time to break. What do you find convincing or not when it comes to these arguments?

Greg Ip: “Ex ante both the transitory and persistent hypothesis were plausible. […] There was a rise in the wage level as firms competed to get staffing to normal levels, and as they did, the job-switcher wage premium faded. No wage price spiral. So the transitory hypothesis has proved more accurate but this was not a foregone conclusion.”

The Economist: “There is much to be said for the supply-side narrative. [..] Some have tried to rescue the Phillips curve [..] Yet this explanation also comes up short, argues Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute […] Moreover, Mr Konczal points to evidence of the supply-side response that enabled this. […] Nevertheless, the notion that Team Transitory was right all along leads to a perverse conclusion: that inflation would have melted away even without the Fed’s actions. [...] Boil the debate down to the question of how the Fed

should have responded to the inflation outbreak, and Team Transitory lost fair and square.” My thoughts about the expectations arguments are here.

Awesome article. I did have another question (which is one I’ve encountered several times online by people who disregard the role of supply). That being: why didn’t real output fall over the past couple years of elevated inflation? Or; how can more be consumed if less was supply was available?