What to Expect of the Expectations Debate

Responding to Larry Summers, sharing some slides, expressing skepticism on the arguments, and setting up some terms for how people will talk about expectations next year.

You can tell the vibes have changed on inflation because we’ve moved from debating who deserves the blame to deciding who gets the credit. In a Financial Times interview last Friday Larry Summers argues that restrictive Fed policy deserves the credit through impacting expectations.

But if events have been more favourable than what I might have expected a year or two ago, I think primary credit should be given to the Fed for having acted relatively rapidly to correct its earlier errors. [..]

So I think that, ironically, if team transitory proves to be vindicated, it will only be because their policy advice was not taken. It will be because the Fed moved strongly enough that [inflation] expectations never became unanchored. And I think that will be the lesson: that strong Fed action that asserts credibility can be surprisingly effective in containing inflation through its impact on inflation expectations, rather than by generating economic slack. [...] I think it is fair to say that it looks like there’s more susceptibility to the inflation expectation term.

Paul Krugman had a response here. This is a big shift for Summers, who in 2022 argued that inflation expectations were backwards inertial (i.e. stuck) at 4.5 percent underlying. (The actual number is less than 2.5 percent as I type this.) Here’s a presentation that I gave at an International Economic Association panel last week that covers the inflation debates of the past 3 years, which digs into that argument. If you are reading this, you might find the slides interesting.

Expectation Stories

You are going to hear more about “expectations” in the year ahead, so it’s worth doing some stage setting for how this debate will go. I’ll certainly be revising my views on this; but this is my first pass to end 2023.

I want to distinguish between three similar, but different, arguments:

The Fed drove the disinflation in 2023 through inflation expectations.

Steady long-term expectations of inflation provided an anchor that helped allow the reopening shock to remain transitory.

The Fed was required to take interest rates into restrictive territory in order to keep (2), in order for long-term expectations to remain anchored. Without restrictive rates, the reopening shock would have become persistent instead.

I think the first is wrong. In current DSGE models that involve forward-looking expectations, you can (controversially) have disinflation uncorrelated with economic activity or unemployment through changes in what people expect inflation to be in the long-term. But that requires actual movement in long-term expectations, one-for-one movements generally. We have seen that kind of movement before, e.g. in the United States during the 1980s. We don’t have any equivalent movement now; there’s simply no variance in long-term measures of inflation in the past year that could justify the disinflation we’ve seen. Without that, the straight-forward version of the first argument doesn’t hold.

I read the second and third as a version of the transitory argument. They concede the thing that is under debate, which is understanding the shock we just went through as the type of shock that is temporary if we don’t screw it up, rather than a demand shock above a more general idea of potential output. These arguments are subsumed under the question “how should policy respond to a supply shock?” which is a good question to be thinking about in the years ahead. But, whatever stock you take in expectations here, they don’t really shake the reopening story at its core.

The second recalls arguments made in David Reifschneider and David Wilcox’s Peterson Institute’s paper “The Case for a Cautiously Optimistic Outlook for US Inflation” in March 2022. This paper feels pretty vindicated, and it's worthwhile to revisit.1 Though they don’t use the phrase ‘transitory,’ it is of the view that the inflation at the time was the result of “a variety of special factors” and “that when [these] adverse shocks stop driving inflation up, the best prediction now is for inflation to return to some ‘anchor’ point [determined by] long-run inflation expectations.”

That expectations help buffer transitory shocks and keep them from becoming embedded is consistent with the idea that inflation and disinflation was driven by the reopening shock. You can find the whole concept voodoo, or an empirical and theoretical disaster (Rudd 2021). But either way, this seems in line with a reopening story.

I’m willing to be convinced on the third, and I assume people will fight about it for years to come. However, there’s two immediate reasons I’m skeptical “that strong Fed action that asserts credibility” was central to disinflation here:

Skepticism One - We didn’t do the Taylor Rule

Rates were not as restrictive as the level implied by the Taylor Rule during the past two years. Rates increased fast, but also because they started from a zero rate. They were higher than what financial markets expected, but the inflation wave caught markets by surprise. They were restrictive, but the basic inputs into a Taylor Rule were more restrictive. Rather than fight about various specifications, here’s the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Taylor Rule utility with its three default values:

Here’s the Fed’s own Monetary Policy Report from June 2023:

If the Fed wasn’t as restrictive as the level implied by the inflation regime it is generally understood to be following, what does that say about the psychology of all this? ‘Powell got really tough’ seems like a stretch. ‘Powell took out insurance against a bad case of a transitory shock becoming permanent’ seems more like the read.

Skepticism Two: Ok, but really, why did nominal wages decelerate?

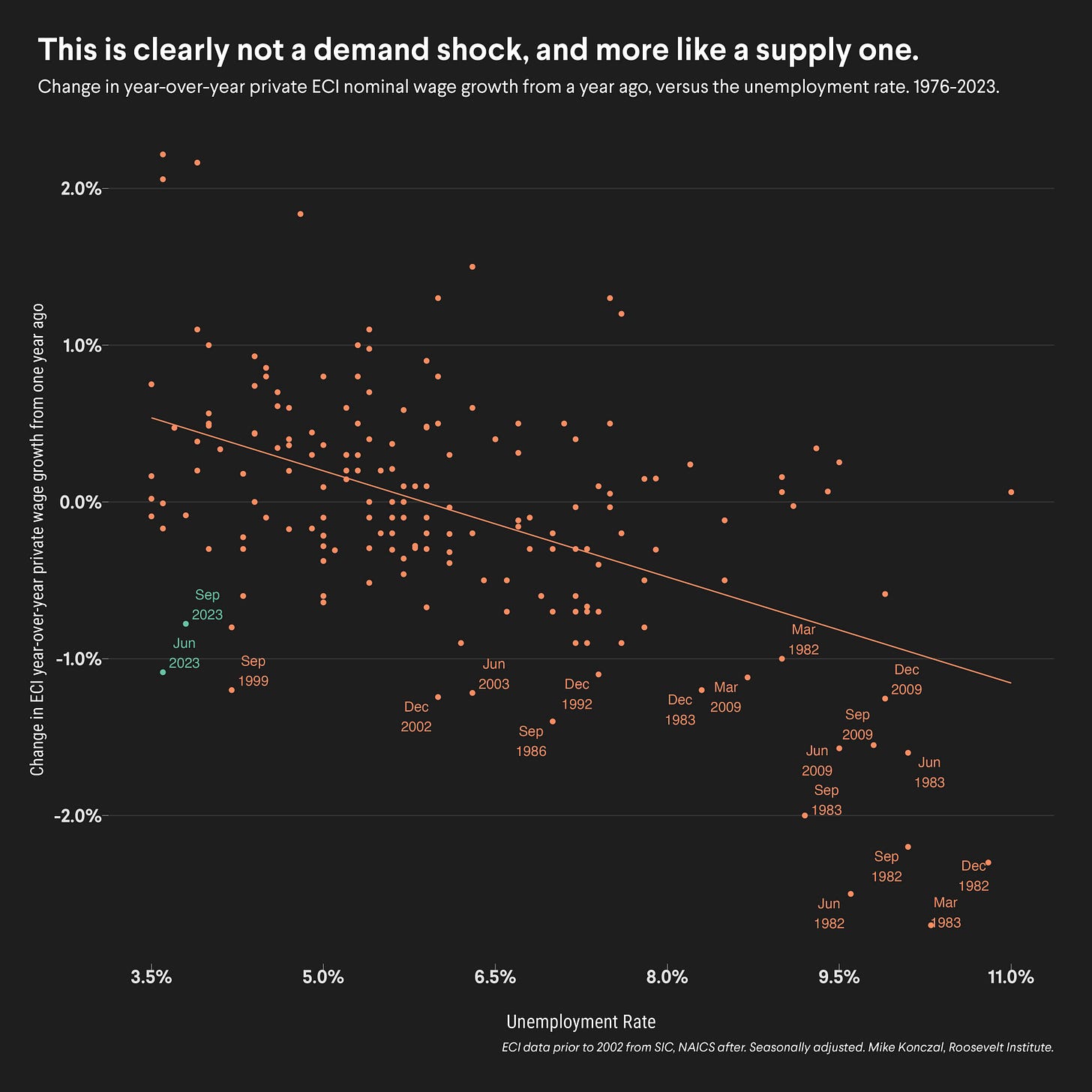

The nominal wage deceleration we saw in 2023 was surprisingly high. Of course, real wages increased because inflation fell faster. But the nominal deceleration is noteworthy.2 I’m still finding the best way to show this, here’s deceleration in ECI from 1976 to 2023 against the unemployment rate:

I still don’t have a clear story for why nominal wages increased and decreased at the rate they did with unemployment below 4 percent. This seems like a central element here, and one reason people thought there would be a recession. I wrote a lot about this debate back in January; this is a central unanswered question for me.

Here are some plausible overlapping answers. Which one is the weakest?

There was a lot of rapid labor demand during reopening. The reopening is over, so we’re back.

Shift from services into goods and then back into services lead to a lot of labor reallocation, with nominal wage increases guiding that. But it’s steady now.

Supply shocks drove the rise and fall, both because people were hired to address them and workers demanded higher wages as a result.

Workers up-skilled into more productive jobs that will become more productive over time; these job-to-job transitions help make growth happen.

The period saw a major one-time weakening of employer monopsony power caused by tight labor markets; the surplus is more equitably shared with workers now.

Labor demand was up a nonlinear wage Phillips Curve and just a little cooling of demand and spending brought nominal wages down.

Workers understood that after Jay Powell’s 2022 Jackson Hole speech (“forceful and rapid steps to moderate demand”) the Fed would be willing to take interest rates into severely restrictive territory to fulfill the stable prices part of its mandate and ensure credibility, and tens of millions of workers decided to lower their nominal wage demands as a result rather than risk the recession.

The last seems like a stretch compared to the others!

Reifschneider and Wilcox: “The statistical analysis in this Policy Brief was conducted before Russia invaded Ukraine. As a result of the war, the inflation situation will probably get worse before it gets better, and could do so in dramatic manner if Russian energy exports are banned altogether. Nonetheless, if the key considerations identified in this Policy Brief remain in place, and if monetary policymakers respond to evolving circumstances in a sensible manner, the inflation picture should look considerably better in the next one to three years.”

Imagine being Reifschneider and Wilcox, working on this paper, and then the invasion of Ukraine happens immediately before it comes out. You could shelf it, or you could slap on a disclaimer and say it’s just one more shock to get through. Kudos to them for doing the latter; they absolutely nailed the call.

In the wages and economy ‘vibes’ conversation everyone discusses real wages, as they should. But I do wonder if the nominal deceleration also played a role in people’s poor sentiment. That said, it’s probably mostly inflation.